The 1990s were an important and turbulent decade for Czechia, but one that has been largely overlooked in architecture. Think “space-age” metro bridges, hotels that resemble giant, colorful cakes, glass office towers that seem like an advertisement for capitalism itself.

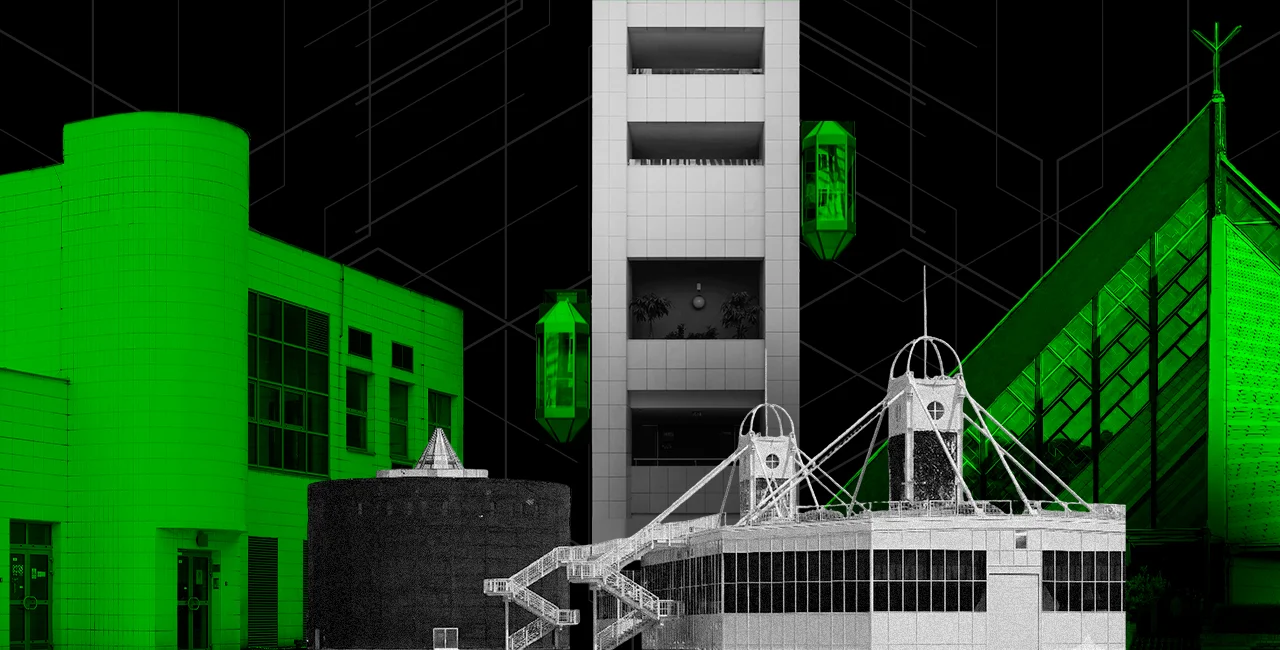

Opening today at the Center for Architecture and Urban Planning (CAMP), DEVADE examines the chaotic 15-year period between the Velvet Revolution and EU accession—an era when Prague’s architecture lurched between serious modernist discipline and garish, wealth-flaunting kitsch.

PARTNER ARTICLE

The exhibition tracks thirty buildings constructed between 1989 and 2004, set against the decade’s social upheaval: the formation of professional associations, the arrival of Western retail culture, and politicians’ evolving rhetoric about architecture.

It wasn’t just about flashy facades; the 90s were when the blueprint for modern Prague was drawn.

“Understanding this period is crucial for the city's future planning,” says Ondřej Boháč, director of the Prague Institute of Planning and Development (IPR). He notes that many issues still discussed by urban planners today, such as the rail link to the airport or the opening of Prague Castle’s gardens to the public, have their roots in this decade of duality.

From Dancing House to DIY fever

The show’s subtitle, "Architecture of Prague Between Rigor and Disco," captures that split personality. On one side stood architects inspired by interwar functionalism and the restrained work of celebrated architect Alena Šrámková, who created some of the era's most recognizable facades.

Leading international architectural firms began operating in Prague for the first time, bringing big names such as Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel, and Ricardo Bofill, who, together with local architects, changed the face of the city and built a number of now iconic buildings, including The Dancing House (1994).

On the other hand, postmodern exuberance imported from an idealized West, complete with gilded frames and conspicuous shapes that loudly announced that communism was over. The very first home improvement stores opened, and, among other things, banks, office buildings with flexible leases, and complex residential projects saw a construction boom.

Inside the show

The exhibition presents historical and contemporary photographs, stories, and artifacts from selected buildings of 1990s Prague, including the Dancing House, the often-criticized Don Giovanni Hotel, Hilton Prague, the Prague Exhibition Grounds with the Křižík Pavilions, Spirála, Pyramid Theater, and the Metro B Bridge tunnel, visually likened to a writhing snake among panel housing blocks.

Archival footage from Czech Television provides context, though the exhibition, complemented by a book by Matěj Beránek and Jan Bureš, aims to examine the nineties "without prejudice and sentiment."

Visitors will also see period objects and art, from Bořek Šípek’s Olga chairs (originally for the Office of the President) to magazines, advertisements, and ironic 1990s memes from the satirical platform Dynamický Blok.

President Václav Havel famously commented on Šípek's work: "I slowly got used to Bořek's art, it took a long time, but then I got so used to it that I cannot be without it,"—perhaps an apt summation of the era's aesthetic uncertainty.

DEVADE runs from Jan. 29 to May. 18, 2026; guided tours, lectures, debates, cinema, and programs for children accompany the exhibit. LINK HERE.

Reading time: 2 minutes

Reading time: 2 minutes