At 11, Peter Kasl defected from communist Czechoslovakia. Decades later, he reflects on freedom 36 years after the Velvet Revolution.

In 2023, a man named Peter Kasl reached out and asked if I would help him write his story. I had studied contemporary Czech history at university and lived with families who had firsthand experience of living under communism. But I had never spoken to someone who had actually escaped, who had crossed borders in secret and rebuilt an entire life on the other side.

Over months of conversations, Peter shared vivid memories of his childhood under communism, the night his family fled through forests and mountains, and the shock of arriving in the United States. He laughed, describing his first sip of root beer—something he still insists tastes like cough syrup—and spoke with pride about balancing his Czech roots and American life.

As the Czech Republic marks the 36th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, Kasl’s story feels especially urgent, a reminder of how fragile freedom once was, and how easily it can be taken for granted. Below is a reflection from Kasl, produced in an as-told-to style.

Life under the Iron Curtain

In our town near Plzeň, most buildings were faded concrete blocks, identical and joyless. Everything looked the same—drab, efficient, lifeless. Food shortages were normal. Bananas, for example, appeared only once a year, and people queued for hours, hoping some would be left by the time they reached them.

Even at a young age, I could feel the fear that hung over everything. Life was quiet, grey, and heavy. People spoke in whispers because you never knew who might repeat what you said, or how it’d be used against you. Neighbors could become informants overnight and were often rewarded for reporting on others. It wasn’t just politics; it was survival.

My parents were not members of the Communist Party. As soon as we started kindergarten, they were summoned by our schoolteachers for lectures about loyalty. They’d smile and nod and say they’d consider joining, never intending to do so, but knowing that saying the wrong thing could destroy our lives.

Thanks to a giant homemade antenna my father had rigged on our roof, we listened to Radio Free Europe in secret and watched television programs from West Germany. Those faint signals revealed a world full of color, movement, and possibility—everything that was missing from the grayness around us.

My parents once received permission to visit West Germany for a week through an arduous process involving gray passports and collateral that would ensure they’d return. This was a scouting trip for them, to see if life was really better on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

When they crossed the border, the contrast stunned them. Shops overflowed with food. Buildings were freshly painted. People laughed openly. They even tried McDonald’s for the first time. My mother later said it felt like walking into a fairy tale.

The dangerous road to freedom

That trip convinced them there was no future for us under communism. They began to plan our escape.

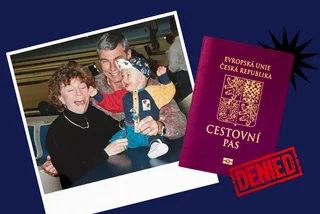

The following year, we told everyone we were going on holiday. My mother had gotten a doctor’s note saying time spent in the water would help her varicose veins, so we were allowed to travel to Yugoslavia, an independent socialist state. On July 4, 1983, we left Czechoslovakia for the last time. I remember waving goodbye to my grandparents, thinking I’d see them in a few weeks. They, like me, were told nothing, for their own protection.

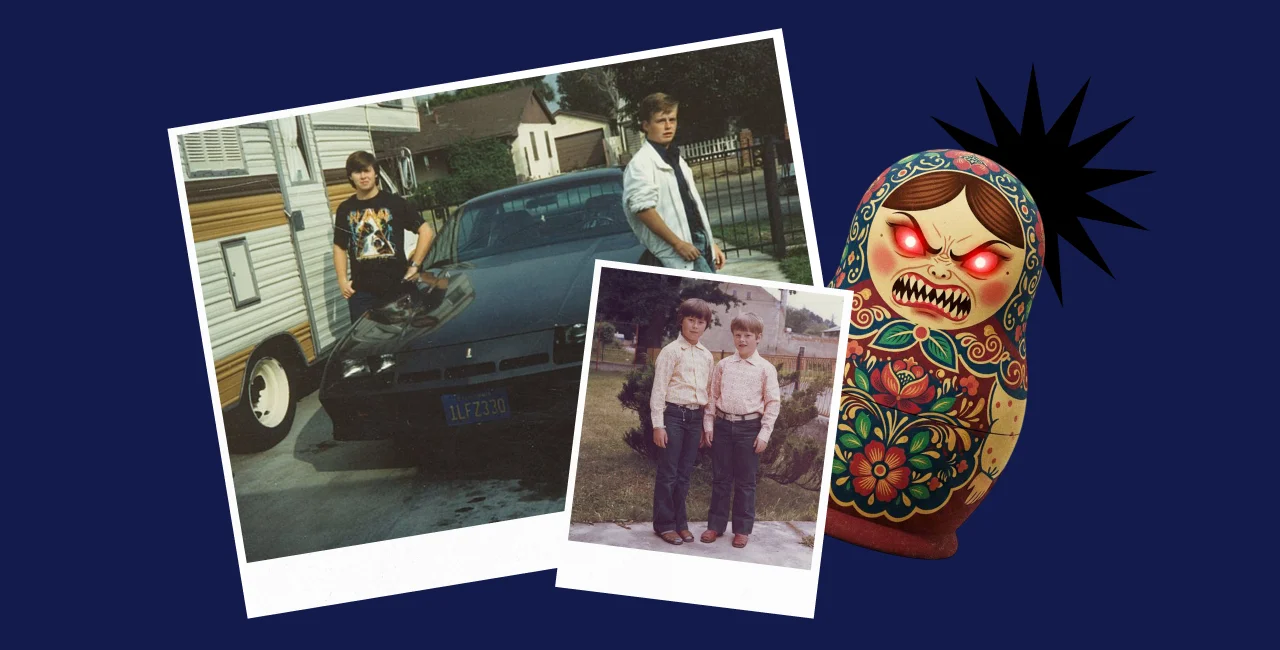

I was 11 years old, and for my brother and me, it was a complete adventure. We camped along Lake Balaton in Hungary, and swam in the Adriatic Sea for the first time. We had no idea what lay ahead of us, even when my father parked our classic car in the main square of Maribor (now in Slovenia), locked it, and walked away for good.

We hiked through the woods for hours, each of us carrying only one small bag. I remember the smell of damp leaves, the silence, my father moving ahead to scout a safe path through the forest.

When we finally crossed into Austria, the first sign of freedom was a vineyard stretching across the hillside, with a white post reading 'Österreich' standing before us. For the first time, we were free.

My parents were nervous when the Austrian border guards spotted us, but they knew what we were trying to do. They gave us food, let us sleep in a hotel, and processed us as political refugees. Within weeks, we reached West Germany, where we waited several months for U.S. asylum.

We arrived in Los Angeles in 1984. I remember how everything appeared so big and colorful, and everyone was so friendly. Adapting to American life was easy for my brother and me, but harder for our parents. They had lived half their lives in fear, but America welcomed us, and soon we built a new life.

We never thought communism would collapse in our lifetime. My parents cried. For them, it was the end of a nightmare they had risked everything to escape.

Five years later, on Nov. 17, 1989, we sat glued to the television again—this time watching students march in Prague, the first spark of what would become the Velvet Revolution. Joy mixed with disbelief.

Learning how to be free

When I returned to the Czech Republic in 1991, it was like time had stopped. Three of my four grandparents were still alive, and our old house was untouched. As I began traveling back and forth to the Czech Republic and Slovakia for work as a hockey scout, I saw a country transforming at incredible speed, but people were still shaking off decades of totalitarian rule.

Freedom had arrived overnight, but you could sense people testing their limits, still unsure how much they could say or who they could trust. The shift from a planned economy to capitalism brought corruption and inequality, and for people who had spent their entire lives under state control, the sudden responsibility of freedom was overwhelming.

Even today, I think many Czechs who grew up after 1989 can’t imagine what it meant to live under communism. That’s not a criticism, but a reminder that freedom is fragile. It’s easy to take for granted when you’ve never known anything else. But for those of us who crossed borders in the dark, it remains something sacred, something we never stop being grateful for.

You can hear more of Kasl’s story on our Expats Extra podcast or find his book, Escaping the Grip of Eastern European Communism, on Amazon.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes