Introducing a new podcast from Expats.cz, Expats Extra. Think of it as the cutting board of our newsroom, where snippets from our stories, behind-the-scenes reporting, and surprising soundbites come together each week. You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Music, or Podbean.

SHOW NOTES: Bits and bytes for Nov. 14, 2025

- Read more about Peter Kasl's great escape and buy his book on Amazon

- Follow journalist and author of Czechs in Berlin, Jana Kománková, and Proti šedi

- Follow Matt Field, British Ambassador to Prague, on Instagram

- See the full lineup of Nov. 17 English-friendly events at Korzo Národní

Alexis Carvajal: The fight for democracy is an ongoing one. But thirty-six years ago this Monday, that effort was in full force in Prague. The Velvet Revolution began on November 17, coinciding with the fiftieth anniversary of the murder of Jan Opletal, when the Nazis stormed the University of Prague after less than a week of protesting. Forty-one years of communism in Czechoslovakia came to an end on November 28, 1989.

Now, more than three decades later, this is still an important day in Czechia. Now called the day of struggle for freedom and Democracy. Celebrations, flood, Narodni trida and all over Czechia throughout the whole day. All of it serves as a reminder of the importance of freedom and those who fought for it. This is Expats Extra, a news podcast from expats, fresh stories, surprising soundbites and extra insights beyond the headlines.

I'm Alexis Carvajal, an intern at Expats.cz. On today's episode, we'll tell the story of one family's flight from communist Czechoslovakia. Unpack what drew Czechs to Berlin before and after nineteen eighty nine, and look at how to celebrate on Monday, even if you don't speak Czech.

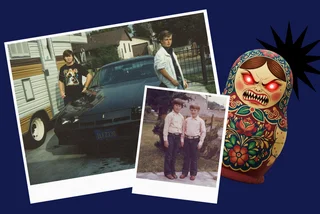

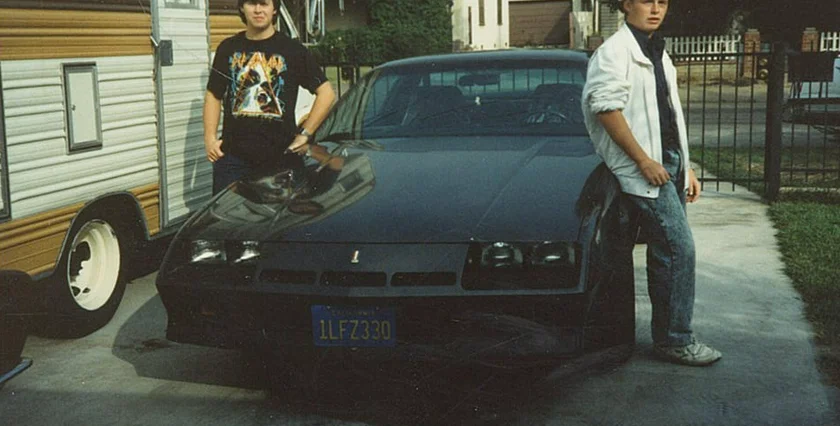

Escaping communist Czechoslovakia for sunny LA

Katherine Rose: Between 1948 and 1989, more than a thousand people emigrated from Czechoslovakia while the country was under communist rule. It was illegal to leave and punishable with up to ten years in prison, but many Czechs and Slovaks left anyway, risking everything to escape an increasingly oppressive totalitarian state.

Eleven-year-old Peter Kasl, was one of them. His family defected in 1983, sleeping in forests, hiking over mountains, and crossing borders on foot before making their way to America. Kasl recently recounted his family’s experience in his book entitled Escaping the Grip of Eastern European Communism: A True Story of Courage, Perseverance, and the Pursuit of Freedom. Kasl was born under communism, growing up in a small town near Pilsen.

Though only a young boy, he was well aware of the tensions that prompted his parents to leave.

Peter Kasl: Even as a young kid, you can feel it. The, uh, the lack of the ability to express your opinion, uh, always felt you're under some, thumb, almost like a physical weight on your shoulders. Be careful what you say, how you say it, to whom you say it. Always being watched.

Political factors weren't the only motivation for departure. Surviving everyday life in Czechoslovakia was also difficult.

PK: There was nothing available. Uh, everything was, uh, a struggle. Uh, whether it was food in a grocery store or just toys, there was hardly any toys for for any kids.

KR: Kasl's parents, Vladimir and Vera, were not members of the Communist Party. They were constantly pressured to join and told that refusing to do so would limit their children's chances for education and future opportunities, knowing it would mean giving up everything for the chance of a better life. They hatched a plan to flee the country.

We left everything behind for freedom

PK: We basically made up a story my parents did to go on a vacation to another communist country, Yugoslavia. Which was which was allowed. My my mother used a doctor's note because she had varicose veins, and the doctor wrote a note, for example, that it would be good for her to bathe in the ocean, the salty ocean, because it helps varicose veins.

KR: Yugoslavia was an independent communist state at the time, meaning the country was separate from the Soviet Union's rule. The conditions there were more relaxed. According to Kasl, though the journey took longer. Crossing the border from what is now Slovenia into Austria was easier than attempting a direct route from Czechoslovakia to West Germany. The castle's escape required meticulous planning. Before defecting, his family held secret meetings with two other families, who would escape with them. To plan the specifics of their journey to.

PK: My parents had to request visas on different time frame, so it did not look like we were coinciding with them, so nobody knew that everything was in secret.

KR: The plan was so concealed that not even Kasl's grandparents could know.

PK: Um, they knew about, uh, that we're going on a vacation. It was very vague. Which is which is going on a vacation. Just keep it simple, because, um, that's the that's the number one fear in commerce. If you tell somebody more than they need to know and they will accidentally reveal it, you can go to prison for just even thinking about leaving.

KR: On July four, 1983, the Kastls packed up their family car and never looked back. The trip included camping in Hungary and time spent swimming along Yugoslavia's coastline. But as an eleven-year-old, Peter didn't fully grasp the gravity of the situation, not until he was in the middle of the woods without a car or a map.

PK: And we spent about four hours in the deep forest looking for a path to Austria. So that's really when it hit me. That's when I realized this is not just an ordinary trip to, you know, a vacation. This is something that I could have never imagined.

KR: Following paths his father cleared ahead, Kasl's family made it to the Austrian border. They eventually found their way to West Germany, spending a year as immigrants awaiting asylum before finally emigrating to the United States. After growing up in landlocked Czechoslovakia, Kasl landed in sunny Los Angeles. The change was overwhelming, but Kasl recalls mostly happy times, a stark contrast to the greyness he lived through in his home country.

PK: Once we made it to the United States, what what really stood out for me is, uh, how big everything is. It was just how everything seemed so, so big and, uh, and, uh, massive. And it just everything was so colorful and nice and, and people were just friendlier. It just it felt like a breath of fresh air.

From ABC, this is World News Tonight with Peter Jennings reporting tonight from Czechoslovakia.

KR: Years later, from his home television set, Kasl watched the forty year reign of communism in Czechoslovakia come to an end. He had quickly adapted to his new life in California, but admits the moment was still bittersweet.

PK: Finally communism ended. Which, by the way, we had no idea. Nobody expected it to happen. When we defected in 1983. We had no idea that in 1989 it was going to come. Come to an end. So it was a surprise. But, uh, again, welcome surprise. But we also had that feeling of, I hope our family is going to be okay, because with those growing pains, bad things have ended. Let's see how things pan out.

KR: Kasl still lives in California today and enjoys the liberties his parents granted him through their sacrifice. He honors those memories through his book.

PK: They are the authors. They. They are the one who made the story possible, uh, with with the with their courage and, uh, to pursue freedom.

KR: And through their story, Kasl hopes to educate future generations in Czechia and around the world.

PK: Freedom is not something that that is given to you automatically. It's something that people have died for in Czech Republic and also in other parts of the United States, United States, obviously. And and people have fought and died for, for, for the freedom that many of them, you know, have currently. So it's important for people to learn the past, learn from it, and preserve the freedom that they currently have.

KR: To learn more about the Kasl's journey to freedom, you can read. Escaping the Grip of Eastern European Communism, now available on Amazon, in print or as an e-book.

A Czech author's love letter to Berlin

Just a short while ago, astonishing news from East Germany, where the East German authorities have said, in essence, that the Berlin Wall doesn't mean anything anymore. The wall that the East Germans put up in nineteen sixty one to keep its people in will now be breached by anybody, one who wants to leave.

Alexis Carvajal: When we think of the events of November 1989, our minds immediately jump to the streets of Prague. But the moment the Iron Curtain truly collapsed happened just eight days earlier in Berlin. What many forget is that Prague played a crucial and often overlooked role in that collapse. That summer, thousands of East Germans fled to the West German embassy right here in Prague, creating a massive diplomatic crisis.

AC: Czechoslovakia pressured East Germany to ease travel restrictions, a move that historians argue effectively triggered the collapse of the Berlin Wall just days before its official fall on November ninth. Prague was an unexpected catalyst in the end of the Cold War. Today we go deeper into that Prague Berlin connection with Jana Kománková, a veteran Radio One presenter and founder of the essential cultural web page Against the Gray (Proti Šedi).

Jana is a continuous voice in Czech culture, and her latest book, Češi v Berlíně: Život za hranicí (Czechs in Berlin: Life beyond the border) is a beautifully told love letter to the German capital and the enduring Czech imprint there. As the wall fell what did that moment symbolize for Czechs living under the communist regime? Jana tells us.

Jana Kománková: It was one of the things, the fall of the wall that showed us that it's possible to change the regime and to just not be under the rule of communists.

AC: The book compares Czechs who left before 1989 with those who left after. Jana tells us about the core difference in the freedom they were looking for in Berlin.

JK: This Berlin was one of those places that was very attractive for those people. The ones who fled before some of them were just illegally leaving the country, and some of them left by marrying a German. After the revolution it was a bit different because it was still more free maybe than the first few months or years, but it was also very attractive as a metropolis full of culture, full of opportunities, not just for artists, but also for other professions.

AC: That artistic and creative connection didn't begin with the Fall of the wall. Jana writes about how Kafka dreamt of freedom in Berlin, and, going back even further, notes the existence of an entire Czech village still nestled inside the city today.

In the middle of Neukölln. All of a sudden, you just step in a small Czech village because there is a place that the Czechs inhabited. When the Czech Protestants many, many years ago left the Czech Republic they were invited by Germans to live there. And they went there, they built houses there and they worked there."

AC: In that enclave of Bohemian Rixdorf, a small village founded by Czech Protestant refugees in the eighteenth century German and Czech languages coexisted. The legacy of those early settlers is still visible today in the street layout and the enduring presence of their institutions. For Jana, the spirit of radical inclusion is alive and well in Berlin today.

JK: There are so many nationalities living there. I think in Prague nowadays, also many foreigners. But in Berlin there is much more of them because basically it's a huge city and it's full of culture, full of inspiration, full of cars, tastes, everything.

AC: Jana, thank you for sharing the deeper cultural connection between these two cities at such a pivotal time of remembrance.

A hard-won holiday for all

Anica Mancinone: Our hands are empty. That simple, defiant chant echoed through Prague's streets on November seventeenth, 1989. Students marched to commemorate International Students Day, honoring those executed by the Nazis fifty years before.

But within hours, that memorial transformed into something far more powerful a protest against communist oppression itself. The march began peacefully, moving from Albertov towards Vysehrad, but as demonstrators left the cemetery and entered the city center at Narodni Trida, riot police blocked their path. What happened next?

The brutal assault on students and peaceful protesters ignited a week of massive demonstrations that became the Velvet Revolution, ending four decades of totalitarian rule. Today, that same stretch of street, Národní Třída, sits at the heart of the annual commemoration organized by the Díky, že můžem. Literally, thanks that we can. The celebration is called Korzo Národní. It's a full-day festival honoring that pivotal moment where Czechs gather to light candles and reflect on hard-won freedoms.

But this year marks something different. For the first time, Korzo Narodni is prioritizing inclusion. Many of the talks, exhibits, and discussion events designed to engage the public with democracy's meaning will be English-friendly. Pavla Umlaufová is the leading PR for Korzo Narodni.

Pavla Umlaufová: We offer the program in multiple languages to make the ideas of the Velvet Revolution and today’s themes of freedom and democracy accessible to everyone, wherever they live here or are just visiting.

AM: So why does this matter? Why should the international community engage with a distinctly Czech national holiday? British Ambassador to Prague Matt Field spoke with us about the importance of discussing this year's themes.

Matt Field: So the topic of this year's Korso Narodni is talk together, and I think that's what's really at the heart of diplomacy and of understanding between people of different cultures. It's talking to each other. That's what makes the difference. And it's one of the things that I love about living here in the Czech Republic is people's openness to talking, to understanding each other's cultures, and I think we all benefit enormously from that.

AM: The ambassador makes it clear this story belongs to everyone.

MF: I think it's great that you are facilitating a program this year that is open to English speakers as well. I think this is really welcome, because the events of November 17 aren't only important to Czech people, they're important to all of us. Their significance still today.

AM: For international residents seeking to understand the history that shaped modern Czechia, Caruso Narodny delivers. Here's what you'll find on Narodni Trida this November 17. First, the conversations live debates with English subtitles tackle crucial questions. Czech foreign policy since joining NATO and the EU democracies, philosophical foundations and even a debate held entirely in English on the role of Serbian students in fighting for freedom.

Then there are the exhibits. No translation required. Tuzeks recreates the atmosphere of Communist era hard currency stores inside period trams. Borders are Not a Promenade documents the travel restrictions that imprisoned an entire generation before 1989. All of this unfolds on that legendary street, Narodni Trida, the very ground where history turned.

The day begins at 10 a.m., with Velvet Brunch offering space to gather and reflect. Commemorations build throughout the afternoon, with music and community events moving toward the most powerful moment of all.

At exactly 5:11 p.m., the crowd performs the Velvet Revolution's anthem, "Prayer for Marta," the song that became the Revolution's heartbeat. November seventeen isn't just about remembering what happened. It's about understanding what's possible when ordinary people stand together and say, our hands are empty, but our voices will not be silenced. Join the commemoration. Join the conversation.

This episode was written, edited, and produced by Elizabeth Zahradnicek Haas, Anica Mancinone, and Alexis Carvajal, with additional reporting from Katherine Rose. Follow Expats Extra wherever you get your podcasts so you never miss a story.

Reading time: 12 minutes

Reading time: 12 minutes