We’re all used to thinking of Prague as a ‘well-preserved’ city. But in fact hundreds of important historic sites have disappeared over the centuries, victims of urban planning, war, or political meddling. In this piece on the Lost Buildings of Prague, we take a look at five that are no longer with us.

The Royal Court

Few visitors taking their morning espresso at Prague’s Obecní dům, that jewel in the crown of Czech art nouveau, realize that they are sitting on the site of a much earlier building. In 1380, Wenceslas IV had a second royal residence built next to the Powder Tower. Its name is recorded in the street which runs alongside the Kotva department store: Králodvorská (Royal Court).

The Royal Court occupied a unique place in Czech history. Here in 1462, King George of Podĕbrady proposed what would have been in effect the first European Union: a multilateral treaty between Germany, France and Italy. It seems, however, that such an enlightened concept was too much for the various parties, not least the Catholic church, and the idea was soundly rejected.

As was the Royal Court itself: in 1484, the seat of power reverted to the Castle; and the arrival of the Habsburgs in 1526 was the final nail in the Royal Court’s coffin.

The abandoned building was purchased by the church in 1631, and for nearly a century and a half survived as a seminary under the direction of Cardinal Arnošt of Harrach (despite a devastating fire in 1689, after which it was remodelled in a neoclassical style). By the final decades of the eighteenth century, a military academy had taken over, and in 1902 – following an ignominious two years as a stable for circus animals and a winter skating rink – this once splendid kingly palace was demolished as part of the city’s new wave of sanitation reform.

The Royal Court

the Powder Tower

The Horse Gate

Long before the National Museum was built, another structure stood at the top of Wenceslas Square. For 500 years, a continuous curtain wall had separated Charles IV’s Nové Mĕsto from the open countryside beyond. It ran from the river in Karlín, down today’s Sokolska and onwards to the ancient citadel of Vyšehrad. From their elevated vantage point half-way along the wall, new arrivals to the city would have witnessed a bustling boulevard thronged with people buying and selling horses; and so naturally enough, the point of access at this particular point – the Gate of Saint Procopius – became known as the Horse Gate.

The Horse Gate

It was one of four fortified bastions which guarded the eastern side of the New Town, though unlike the others there was no drawbridge. After extensive alterations in the 17th century, the gate was finally replaced in 1836 with a grand empire-style colonnade designed by Petr Nobile, also the architect of the Old Town Hall

By the end of its life, the gate had become part of a garden promenade, replete with cafes and restaurants; and a walk along the wall became a popular weekend pastime. However, with the increasing expense of maintaining the ancient fortifications, Franz Josef I decreed that Prague should be an open city, and had the whole lot dismantled. The Horse Gate was demolished in 1875, but when plans were drawn up for the National Museum, the architect cleverly mimicked the three arches of Nobile’s design in the lower range of the new building, so a memory of the old gate remains even to this day.

National Museum

The Old Town Hall

Fans of Mission Impossible will remember the part where Ethan Hunt spectacularly blows up a glass fronted restaurant and then flees into the night across the Old Town Square. In 1945, once they knew the game was up, the retreating Nazis tried a similar trick when they detonated the Old Town Hall, adjacent to the Astronomical clock.

The Old Town Hall

What they destroyed has never been replaced. Arguably it was no great loss: the 19th century neo-gothic structure – which had replaced an earlier mediaeval hall – was a relatively recent, and comparatively ugly addition to the square’s architecture. Moreover, its removal opened up a view of the church of St Nicholas which had obscured for at least a hundred years.

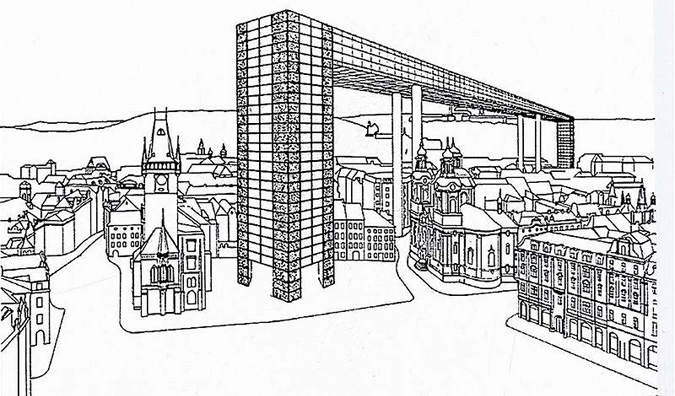

Throughout the last century, there were multiple plans to rebuild the town hall. In 1909, Josef Gočár designed an enormous ziggurat, hopelessly out of scale and higher then the clock tower. In 1987, Milan Knížák proposed an extraordinary La-Défense-type arch soaring over the rooftops of the old Town, with one upright planted on the footprint of the old hall, the other next to the Jewish cemetery.

Milan Knížák’s proposal of La-Défense-type arch

It seems that leaving well alone is not an option. If a new structure does eventually fill this gap in the Old Lady’s teeth, it is now more likely to be a faithful reproduction of the original 14th century hall. This would certainly be in keeping with the current plan to restore other original features to the Old Town Square in the near future. Better still, why not keep it as an open space?

Denis Station

The pre-eminent French expert in Czechoslovak affairs, Ernest Denis literally helped put Czechoslovakia on the map in 1918. His tireless work in helping to establish the First Czechoslovak Republic was rewarded the following year when Prague’s magnificent North-Eastern railway terminus was renamed Denisovo Nádraží in his honor. At 115m in length, this monumental train station was considered amongst the finest in Europe, if not the world.

Its façade was a triumphal triple arch, embellished with four Corinthian columns each topped off by an allegorical sculpture symbolizing Trade, Science, Industry and Economy. Above the pediment appeared a further allegorical group surrounding the personification of Austria (the station had been originally constructed in 1872) . Inside was a glorious panoply of stucco mouldings and chandeliers, with a first floor restaurant and murals depicting the towns through which the railway passed.

Denis Station at Těšnov near Florenc

Alas for Ernest Denis, his association with the railways was only a brief encounter. A year before they destroyed his statue in Malostranské náměstí, the Nazis also erased his name from the station, renaming it, predictably enough, Moldau Bahnhof. The Soviets were no kinder when they reinstated its original name: Prague-Tĕšnov. Without question, had it survived until 1989, this glorious building would once more have been called ‘Denisovo’, after that great friend of the Czechs. But by the time of the Velvet Revolution, it had already been reduced to rubble – demolished to make way for the Wilsonova highway.

Těšnov near Florenc in 2012

Hortus Angelicus: The Angel’s Garden

The main Post Office on Jindřišská is a fine example of neo-renaissance architecture from the 1870s, with its interior murals of flowery figures telling the story of postal communications. But did you know that the plot on which it is built was also the site of the first botanical garden in Central Europe?

Today, the only clue to the garden’s existence is in the street that once ran along its north-east border. Nowadays named Politických vězňů (Political prisoners street), it was at one time called Platea Angeli, after the 14th century pharmacist, Angelus of Florence. Invited to Prague in 1346 by King Charles IV, Angelus and his descendants were given the right to ply their trade in Malé Námĕstí, just off the Old Town Square. This specially cultivated garden, from which he plucked his herbal remedies, became famous throughout the civilized world.

Angelus was only one of a huge number of Italians in Bohemia at the time. Florentines were considered to be highly educated: in nearby Kutná Hora, the Royal Mint was known as Vlašský Dvůr (Italian Court) because of the sheer number of Florentine silversmiths working there. And in Prague itself, the district north of Jindřišská has for many hundreds of years borne the name of Angelus’s home city. It’s called Florenc.

One of the great things about Prague is that it is not some well-preserved Disneyland: architecturally speaking, it is always on the move, as these examples show. Some districts, like the Jewish quarter, are lost forever; others retain a street pattern or a single exposed building like the Výtoň customs house at Podskalí. What examples do you know of? Send in your suggestions for a possible sequel!

Related articles

Top Ten Ugliest Buildings in Prague

Alex Went is the curator of The Prague Vitruvius an illustrated guide to the city’s architecture.

Related articles

Reading time: 7 minutes

Reading time: 7 minutes

English

English

Czech

Czech

Ukrainian

Ukrainian

Spanish

Spanish