The word ‘mafia’ comes up a lot in casual conversation with friends. The way some people tell it, organized crime has its long fingers in all manner of pies. Sometimes it sounds like unsubstantiated conjecture. Other times, well…certain names come up, and those names are associated with deeds that are more than rumor.

Before delving into those stories, it’s important to remember how the term ‘mafia’ is being used in this context. The situation is not simply a central European version of The Sopranos. Certainly, the figures connected to this activity have been accused of gangster-like behavior. However, more often they are accused of circumventing the established conventions and rules of business, using political contacts who are allegedly paid off or intimidated into furthering their business interests. Sometimes, these interests can seem quite banal and un-mafia like until it becomes clear how they, supposedly, achieved their goals.

Mrázek: the “Godfather”

Until his murder on January 26, 2006, František Mrázek was considered to be the head of the Czech Republic’s underworld. The word ‘considered’ has to be emphasized because František Mrázek was never formally charged with any crime after 1989.

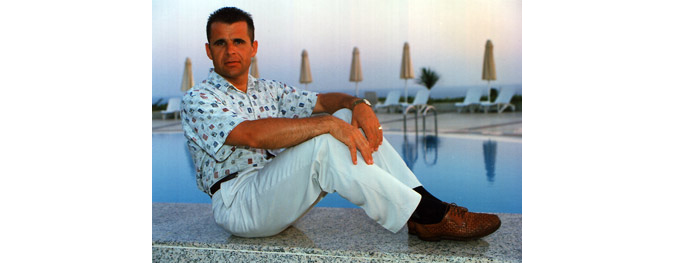

František Mrázek

Prior to the revolution, he was arrested for smuggling. After the change in regime, his wealth and influence only grew and the source of both has been questioned by some in the press, especially the investigative journalist Jaroslav Kmenta. Kmenta has written numerous articles and a trilogy of books on Mrázek called Kmotr Mrázek (Godfather Mrázek), the facts of which some people have disputed.

One affair, which Kmenta recounts in the first book, concerns the way in which Mrázek obtained the Eggenberg brewery, based in Český Krumlov. The brewery was sold at auction in 1991. Mrázek and his business partner Jiří Shrbený obtained the company for 75 million CSK. According the Kmenta, the company was valued at 700 million CSK. He also states that a fellow bidder alleged to being offered 5 million crowns to withdraw his bid. Neither the man who offered the money nor the bidder are identified by name in the book. Any sense of wrongdoing is more implied. Namely, how did Mrázek come to purchase the brewery for such a low price?

Other Business Interests

Kmenta also attempts to implicate Mrázek in the acquisition of the building firm Inženýrské a průmyslové stavby (IPS) by Luďek Sekyra’s Středoevropská Stavební. In order for Sekyra to purchase IPS, he needed an extension on credit from Investiční a poštovní banka (IPB). The Swedish firm Skanska was the other potential purchaser of IPS.

According the Kmenta, Mrázek set up a meeting for Sekyra with Václav Klaus, who was the Chairperson of the Chamber of Deputies at the time. In the transcript of the police wiretap published in the book, Sekyra claimed that Klaus – who is identified by the code name Professor – would speak with the head of Nomura, the Japanese bank which owned IPB. However, it should be stressed that Klaus’ involvement has never been confirmed due to a lack of evidence [http://zpravy.tiscali.cz/sekyrova-praha-praha-prohnila-47721] (link in Czech). Sekyra also claims Mrázek’s role in the affair was “marginal” (link in Czech). Following this affair, IPS was sold to Skanska, and IPB went into receivership in a dramatic daylight raid by police (in Czech).

Regarding his connection to Setuza and Tomáš Pitr, the wiretaps published in Kmenta’s books certainly reveal that Mrázek and Pitr were in contact. In an interview following Mrázek’s death, which was published in the third part of Mrázek Kmotr, Pitr described the slain businessman as one of his closest friends, but what did that friendship entail? According to Kmenta, the pair embezzled about one million crowns from Setuza by moving money on to the account of Eggenberg (link in Czech).

Fall of the Godfather

On the evening of January 26, 2006, outside the headquarters of his company in Durychova Street in the district Lhotka, Mrázek was shot once directly through the heart by an unknown assassin. A doctor tried to save his life, but Mrázek died within a few minutes. After a little over three years of investigation, the police were unable to find any evidence to prosecute someone and so closed the case. This was not the first time Mrázek was shot at and the manner of his death has done more than anything to sustain speculation about what he did in his life.

Kubice Report

In May that year, the director of the organized crime unit Útvar pro odhalování organizovaného zločinu (ÚOOZ), Jan Kubice, approached Czech MPs with what has since become known as the ‘Kubice Report” (in Czech). The report among its details includes information about the investigation into the murder of Mrázek.

Jan Kubice (on the right)

Four possible motives for the murder were outlined in the report: the sale of Setuza, so Tomáš Pitr was a person of interest; rivalry with Radovan Krejčíř, the fugitive Czech businessman; revenge for murders which Mrázek had ordered; Mrázek’s business practices, or his alleged role in the dismissal of Stanislav Gross. The report also named Václav Kočka, operator of the Prague Matějská Fair and alleged adviser of Jiří Paroubek.

Suffice to say the accusations were political dynamite. Then-prime minister Jiří Paroubek, held a special press conference to deny the allegations, especially those connecting him and his party to the underworld. Paroubek maintained a lengthy campaign against Kubice. When the former police officer was made Minister of the Interior in April 2011, Paroubek called the appointment “scandalous”. Later that year, he published a book Český Watergate in which he claimed the Kubice Report was worse than the wire-tapping scandal of News of the World.

Read also: Get Rich Quick: Czech Fraudsters – Three of the Czech Republic’s most notorious businessmen

Another Shooting

The launch of Český Watergate was by all accounts a peaceful affair. The same cannot be said of Paroubek’s book launch in 2008 at the Monarch Restaurant. At the event, the son of the aforementioned Václav Kočka, Václav Kočka Jr., was shot by Bohumír Ďuričko, was also named as an acquaintance of Paroubek’s in the Kubice Report.

Bohumír Ďuričko

In April 2009, Ďuričko was sentenced to 12.5 years in prison, where he wrote a book, the rights of which were bought by a group of people allegedly close to Paroubek. In a strange twist, Paroubek’s online magazine Vaše Věc published an online version. The content doesn’t seem to shed much light on Mrázek’s shooting.

Godfather Part Two

Sadly, Mrázek is far from the only case of questionable persons having ties with government. Nor is it an issue only for the Social Democrats. In March this year, the newspaper Mladá Fronta Dnes published part of the conversation between former Prague mayor, Pavel Bém, and businessman and ‘lobbyist’ Roman Janoušek (the term lobbyist has a sinister connotation in the Czech Republic, meaning someone who tries to influence government by underhanded means.)

Of particular concern is how the pair decided the fate of the company Navatyp following the death of the company’s founder and director, Richard Navrátil. The company was responsible for a number of developments in Prague and was worth about 500 000 000 CZK. According to the conversation, Bém, after discussing the death of Navrátil, asks Janoušek for instructions.

Around the time the case broke in the press, Janoušek was involved in a car accident. His Porche Cayenne hit a Volvo in the rear. Janoušek allegedly fled the scene by driving off, but the driver, a Vietnamese woman, chased him to a nearby traffic light where he’d stopped. She stood in front of his car to prevent him fleeing further and he apparently rammed her twice with his car and drove off, only to be arrested nearby, at which time he was found to have a blood-alcohol level of 0.22%. He was later charged by police with causing grievous bodily harm and menace due to intoxication.

Reading about cases like this I understand why my Czech friends and family are despondent about the political scene here. But is it totally hopeless? You tell us.

Related articles

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes