The historical Jewish quarter of Prague has long been a tourist attraction. Today, people come to connect with family roots or to get a glimpse of a Prague that has long been associated with mystery. What few probably realize is how much the quarter has changed.

From Establishment to Demolition

When Jewish people first arrived exactly in the Czech lands is contested. The earliest written reference is from 965 by the merchant and diplomat, Ibrahim ibn Yaqub. Livia Rothkirchen, in her book, The Jews of Bohemia and Moravia: facing the Holocaust, suggests that settlement could have been before the land became Christian. Whatever the precise date, from the moment Jewish people settled until the razing of many buildings in Josefov, the fortunes of the community in Prague were subject to the political turmoil of the region.

When the Crusaders passed through in 1096, they attacked the local Jewish population in a series of pogroms, disrupting what Yaqub had described as a prosperous community. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the community’s situation improved when they became servi camerae regiae, literally “servants of the king’s chambers”. For the protection this entailed, they paid increased taxes.

In 1389, the notorious Easter Pogrom occurred. Non-Jewish townsfolk entered the quarter, murdering and pillaging. At the end of the massacre, around 1500 Jewish people lay dead, perhaps more. Their houses were burnt to the ground and possessions stolen.

Against this backdrop of violence and persecution, the community developed and, at times, prospered. By the sixteenth century the quarter became the a center for Talmudic learning. Perhaps the most famous Jewish scholar from here is Rabbi Loew, also known as the Maharal of Prague. Though he is associated with the legendary golem (the remains of which are said to be in the Old New Synagogue), his real life work and thought touched on many aspects of Jewish life including religious observance, ethics, and education.

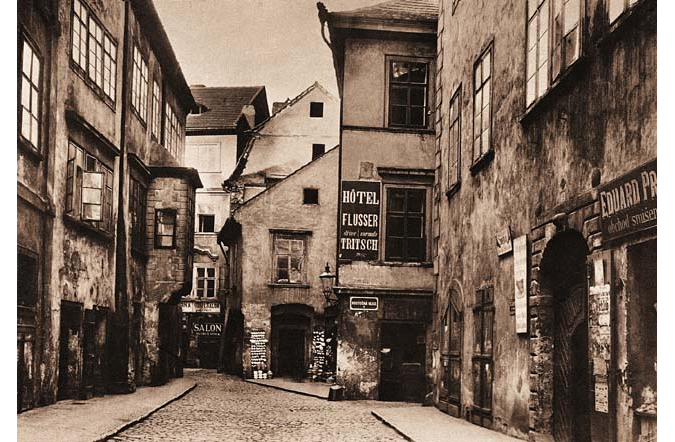

The Maislova street stretched from Staroměstské náměstí to Josefovská street. Photo from 1896

The dual experience of increasing freedom and continuing hostility was a constant theme through to the nineteenth century. Jews were admitted into universities and into political roles, such as Moses Israel Landua, who was the first Jew elected to the Prague City Council in 1849. Yet, Jewish people had to face antisemitism from the Catholic Church and deep-seated mistrust from people in the countryside.

Reasons for the Demolition

By the end of nineteenth century, the city’s leaders thought it necessary to improve the living conditions of the district and modernize the city. This project was known as the asanace. Peter Demetz in his book, Prague in Black and Gold: the history of a city, offers some fairly startling facts about living conditions in the quarter which prompted this measure. Firstly, it was cramped with 1822 people per hectare.

Sales Lead: High-Performance Computing & AI

erelict housing, a very dense conglomerate of houses and unhealthy overopopulation were the official reasons for the clearance move. Photo, J. Eckert

By way of comparison, the densest part of London had a population density of 642 people per hectare in 2009. About two thirds of the apartments in Josefov had only one room. Utilities were in short supply. Water was often pumped from shared wells and on average one toilet served five to ten people.

A newspaper article from Národní listy published in 1883 described the district as such: “We do not advise a citizen who has weak nerves to venture into the labyrinth of old black canals, covered with centuries of dirt, tumbledown houses or those hammered together from five, sometimes six to ten parts, each of which almost dates from another century – and beware anyone whose stomach is somewhat intolerant, go to the streets, where heavy, leaden air can be cut, simply go to our ghetto.”

Perhaps a better record of the area are the many photos which were taken.

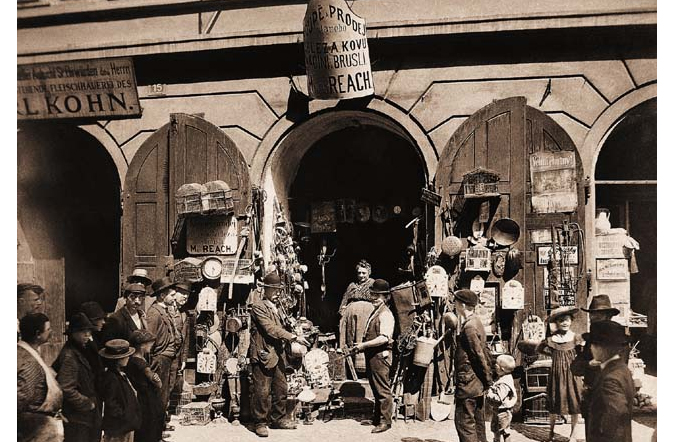

This link and this one both provide a sample of the conditions of the buildings at the time many which date to the Renaissance or even earlier. A more comprehensive sample of photos can be found in The Lost Jewish Town of Prague by Hana Volavková and Pavel Bělina or Židovské Město pražské na vedutách, fotografiích a pohlednicích (The Jewish Town of Prague in vistas, photos, and postcards) edited by Edmund Orián. Both books provide commentary on the district, along with many pictures of its narrow streets and courtyards along with images of daily life in the quarter.

While at first it might be assumed that these descriptions and portrayals of the quarter were fueled by prejudice, it should be pointed out that local residents, who were by this stage mostly non-Jewish, also thought the quarter needed cleaning up. Some even likened it to a ‘suppurating ulcer on the face of Prague’. Suffice to say, when Prague City Council passed the law in 1893 to carry out the asanace (clearance), most residents agreed. Some of them even formed an association to protect their interests during the period. Furthermore, one of the main champions of the demolition was Dr. Augustin Stein, an important Jewish community leader.

Despite local support, there were those who were opposed to the asanace. The playwright Vílem Mrštík, writer and journalist Jaroslav Kamper and novelist Václav Hladík issued a manifesto in 1896, asking the city’s councilors to preserve its historical character and its ancient atmosphere. A year later, Mrštík released his pamphlet “Bestia trimphans” (in Czech) in which he sees the plan as the triumph of brute force of aesthetic values. Despite his and other impassioned pleas, the plan went ahead.

The demolition of houses near the Church of the Holy Spirit and the Spanish Synagogue. Photo, J. Kříženecký, 1912

Demolition Derby

It must have been disheartening for those who opposed the demolition to see that when it started in 1896, no one rose up in protest. On the contrary, excursions were organized for what was seen either as Prague’s modernization or at least a spectacle of destruction.

Surrounding areas of Old New Synagogue. Photo from 1902

By April 28th, 1897, 22 buildings were pulled down, half of them on Maiselova Street, which still remains today. The most dramatic change was the creation of Pařížská Street, which leveled a large part of the former district. Other streets and the lives they were a backdrop to vanished as the centuries old buildings were knocked to the ground.

The process of asanace was extended until 1943, though the bulk of the clearance was done by 1914. Once over 128 buildings were demolished. In a macabre twist, the Nazis intended to preserve what remained of Josefov as a “museum for an extinct race” had their murderous plans been fully realized.

Josefov was known for its little shops of various types, where one could find anything that could possibly cross their mind. Photo, J. Eckert

The buildings that remain are the ones which have been deemed of greatest historical and cultural importance. They are six synagogues: Old New, Pinkas, Spanish, Maisel, High, and Klaus, as well as the Ceremonial Hall, the Old Jewish Cemetery and the Jewish Town Hall. Another important site is the place of Franz Kafka’s birth. Though it is not the actual building he was born in (the original burned down in 1897), the one which was built to replace it still stands.

Visiting Today

The Jewish Museum of Prague maintains the Pinkas, Spanish, Maisel, and Klaus Synagogues, Ceremonial Hall and Old Jewish Cemetery as part of its permanent exhibition. A ticket to all the sites is 300 CZK for adult (120 CZK with an OpenCard). Entrance to the Old New Synagogue is 200 CZK. Tickets can be bought from any of the sites. The sites are closed on Saturdays and Jewish Holidays.

Related articles

- 10 Travel Articles That’ll Get You Excited for Autumn In the Czech Republic

- VIDEO: Amazing Recreation of 14th-Century Construction of Charles Bridge

- Prague Is the Cheapest City In Europe for Ballet, Opera, Art

- Český Krumlov Mulls Over Charging Tourists a Toll

- New Travel Guide Puts Czech Monasteries On the Map

Reading time: 6 minutes

Reading time: 6 minutes

German

German