The new Netflix psychological thriller Bandersnatch, written by Black Mirror creator Charlie Brooker, was released December 28 to mixed reviews — some critics found it too gimmicky while others hailed the show the “tv of tomorrow.” Set in 1980s England, the plot focuses on a young programmer who dreams of adopting a choose your own adventure book into a revolutionary videogame.

Audience participation in matters of plot is nothing new — beyond the choose-your-own-adventure books, written in the second person and presenting readers with a decision to make every page or two, there were Sega CD “video games” like Night Trap, as well as an attempt by a company called Interfilm to bring the format to mid-90s cinema-goers, with audience members voting on plot twists through a joystick device connected to their seats.

There was even a 1995 20-minute film Mr. Payback written and directed by Back to the Future producer Bob Gale and starring Christopher Lloyd, which was billed as “the world’s first interactive movie.”

Kinoautomat: the world’s first interactive movie whose plot and story are determined by the audience.

A Czech invention first presented at the Expo ’67 in Montreal.https://t.co/X8gl7faJ7a#Czechoslovakia#Cinema#MovieHistorypic.twitter.com/K54quCZt10— History of Communism (@HOCommunism) May 16, 2018

Not quite: the world’s first interactive movie where plots are determined by the audience premiered in 1950s Czechoslovakia, offering people the only free choice they could make in the communist regime.

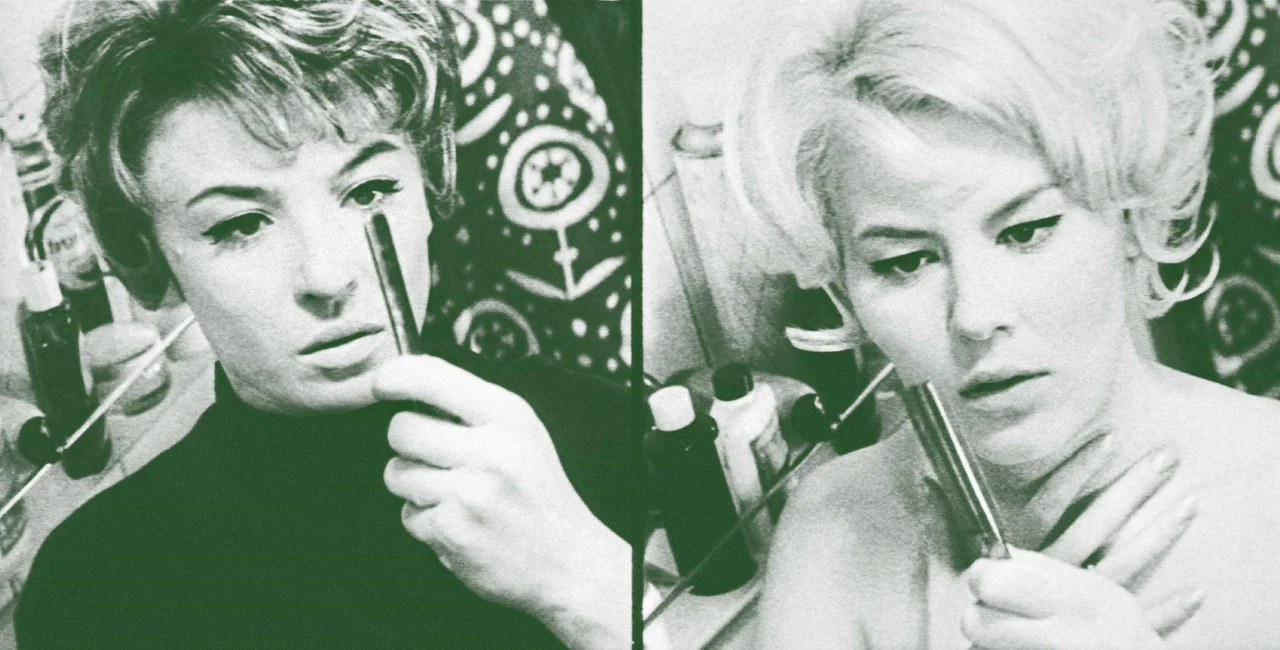

The brainchild of co-director Radúz Činčera, the Czech-invented Kinoautomat concept debuted at the World Expo in Montreal in 1967 and toured the globe for seven years. Each viewer was given a small controller with two buttons and could vote for one of two options to determine the course of the film at selected intervals, during which the picture would freeze and a moderator would walk onto the stage.

The film, Man and his House (Člověk a jeho dům), was a huge success at the Expo with people waiting in queues for several hours to see the biggest hit of the festival. While not a cinematic masterpiece, it was definitely a landmark one. (The trick? With two projectors running the film always doubled back to the same choice, just via a different path. The projectionist simply switched a lens cap on one of the projectors based on the audience decision.)

By the 1990s, Radúz Činčera seemed to have been mostly forgotten, along with his film. He created another interactive film for the 1990 World Expo in Osaka; in Cinelabyrinth, viewers again chose the course of the movie — but this time, they physically got up and walked through a door to an adjacent theater to watch how their decision unfolded. Of course, everyone ended up in the same cinema for the finale.

Before his death in 1999, Činčera staged a multimedia presentation in Prague’s St. Michael’s Church that drew heavy criticism for perceived misuse of the church.

Last year Kinoautomat was screened in honor of 50 years since its inception in a number of countries around the world; his daughter Činčera’s daughter Alena Činčerová was responsible for restoring the film and bringing it to a new generation of audiences.

For more information, you can read our 2009 review of Kinoautomat here.

Reading time: 2 minutes

Reading time: 2 minutes