One of Prague’s jewels is Letná park, with its winding paths, large open fields, tennis court, beer garden and various public sculptures.

One of its legacies is the base for a long-gone statue of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin. The stonework now serves as a skateboard court and the home to a giant modern metronome.

PARTNER ARTICLE

Going back in history, the park saw the beginnings of the city’s now massive public transit system, which began with a modest cable car.

There have also been plans that never were fulfilled, including sawing Letná in half to make a wide avenue and building a modern blob-like library.

Stalin

Long before the top of Letná was home to skateboarders, there was a giant granite statue of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin with a line of workers and scientists behind him.

The statue, in place from May 1, 1955, until the end of 1962, was the largest group statue in Europe and weighed 17,000 tons. It was made of 235 granite blocks. One button on Stalin’s coat was a meter wide.

Work on the original statue began in 1950. Stalin died in 1953, and by the time the statue was finished, the cult around him was already falling apart and the monument was a source of some embarrassment until it was destroyed. Residents of Prague referred to the statue as the “line for meat” (fronta na maso), as it resembled people waiting outside a shop to get goods in short supply.

The statue brought bad luck to many of those involved with it. Sculptor Otakar Švec killed himself just before it was unveiled. The man who modeled for Stalin, an electrician from Barandov Studios, faced endless ridicule and turned to heavy drinking, which precipitated an early death.

Authorities at the time of the statue’s destruction forbid people from filming it and only a few pictures were clandestinely shot capturing the massive explosion propelled by 800 kilograms of explosives.

The pedestal is still in place, and currently supports a giant metronome called Time Machine.

The base of the monument was built as a bomb shelter, and in the 1990 was home to a pirate radio station called Radio Stalin and was later a rock club and a venue for fights.

A statue of Michael Jackson stood there briefly on the same spot in 1996 for the launch of the HIStory tour. Jackson’s concert took place on Letná Plain.

A cultural center and outdoor bar called Stalin has recently been holding events at the base of the plinth.

In 2016, a Styrofoam replica of the statue, scaled down so it could look full size with camera tricks, was built on the original base by Czech Television. It was used for the film Monstrum, which told the story behind the making of the statue.

Concerns over structural integrity caused the base and the top, used for skateboarding, to be closed temporarily in September 2019. Current plans include possibly opening up a museum dedicated the memory of totalitarianism in the base.

The Metronome

The 23-meter tall metronome in Letná has become one of the most iconic images of the Prague. It is visible from the edge of Old Town Square, looking down Pařížská Street, across Čechův most, and on top of the plinth where the statue of Stalin used to stand. The actual name of the artwork is Time Machine (Stroj času), the most people call it the Metronome.

It was built in 1991 according to a design by Vratislav Novák, and it is in the process of being restored. The pendulum was recently put back in place, and it should be back swinging away the hours in a few weeks. The Metronome was made for the General Czechoslovak Exhibition (Všeobecná československá výstava) in 1991, which marked the 100th anniversary of a similar exhibition in 1891, the General Land Centennial Exhibition (Jubilejní zemská výstava v Praze).

Both exhibitions took place in Holešovice. The 1991 exhibition was not successful, and the organizing company ended in bankruptcy.

Today, the Metronome is actually privately owned and operated by Pražská správa nemovitostí.

The original idea was more complex, but technically unfeasible at the time. A laser beam from Old Town Square was supposed to light up the Metronome, visually linking the historical past to the ever-ticking future. The concept was revived briefly as part of the 2013 Signal festival of light art.

In 2003, the Metronome was used to promote the Czech Republic’s EU entry by oscillating between the words “yes” and “no.”

Novák, who passed away in 2014, graduated from Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, and since the 1960s has been known for his mobile sculptures and kinetic objects. For a long time he lived in a former church in the town of Rýnovice, and used a converted morgue as his artistic studio.

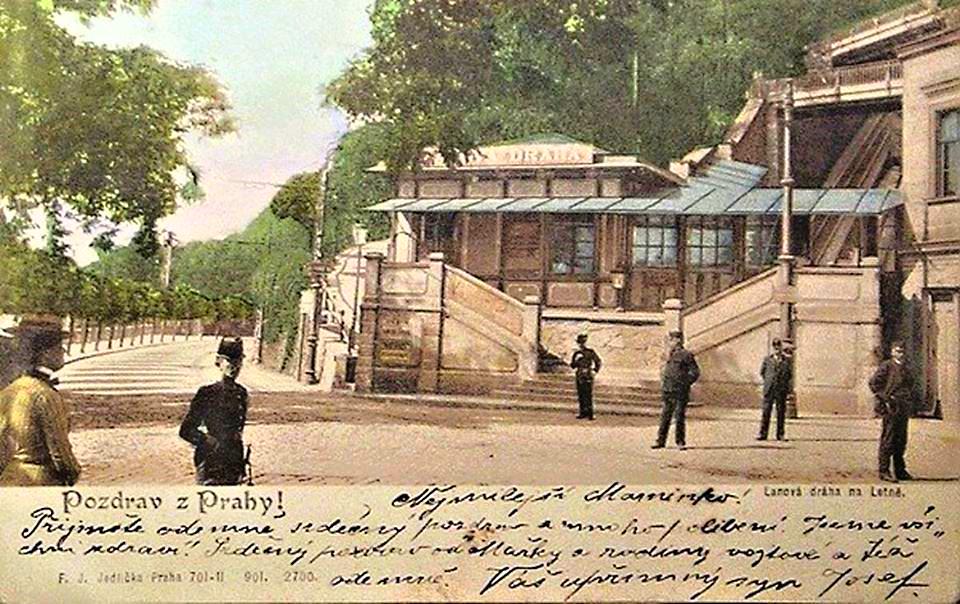

The Letná funicular

A cable car used to run up the side of Letná, for those who didn’t fancy the rather steep hike. The remnants of the upper landing have recently been restored into a lookout platform, and it can be found at the edge of the beer garden.

Prague’s first cable car opened on May 31, 1891, and operated until 1916. It was definitively abolished in 1922. It led from the long-gone bridge Most císaře Františka Josefa I., approximately where Štefánikův most now stands, and took people to Letenský zámeček, which even then was a popular hangout.

The cable car, on a double track, was operated by Správní rada lanové dráhy na Letnou, which was the first city-owned transit company. Other trams and buses were privately operated. In 1900, it was taken over by Elektrické podniky královského hlavního města Prahy, the forerunner of the current Prague Public Transit Company (DPP), and electrified in 1903.

From 1926 to ’35 there was a moving wooden staircase in the space where the cable car used to run. It can be seen in the 1931 film Men From Offside (Muži v offsidu).

Prague’s first electric tram

A short walk across the park took people from the funicular to Prague’s first electric tram, which linked Letná and Stromovka. About a meter of the original tracks still stand, with a small stone maker explaining what they are. It is near a carousel, which is slowly being restored.

The electric tram was the idea of inventor František Křižík, operating from 1891 to 1900. It was a prototype design, built to coincide with the 1891 General Land Centennial Exhibition. Previously, trams had been pulled by horses.

The track was a monorail, with the tram going back and forth on the short route. The trip, with a speed limit of 10 km/h took about five minutes.

The plan to cut Letná in half

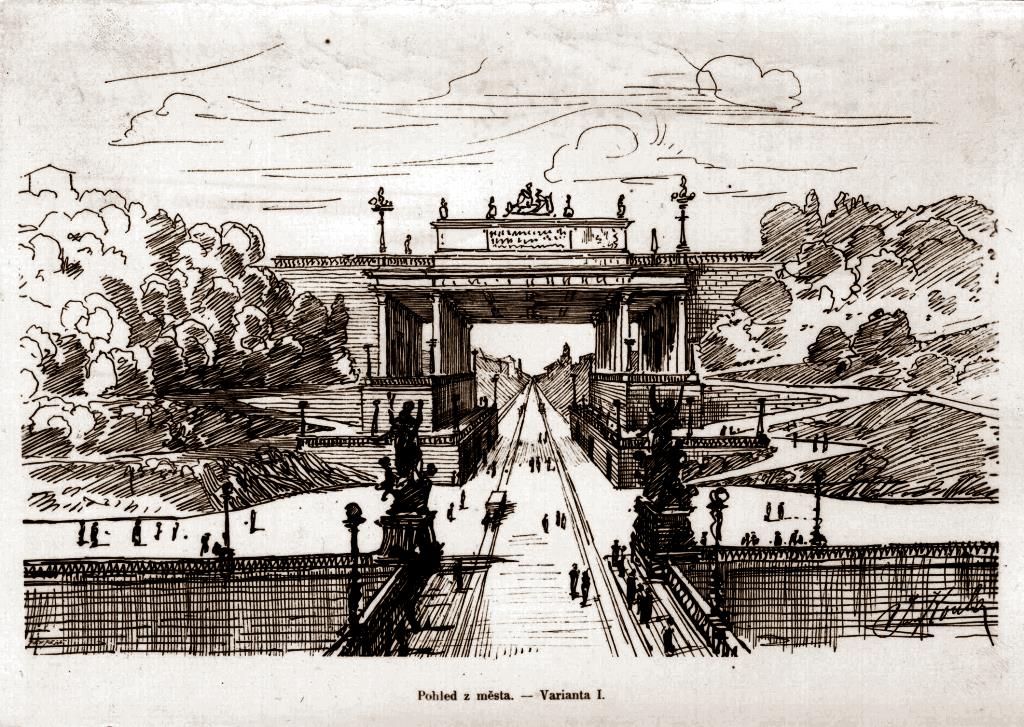

Architect Jan Koula in 1907 had a vision for a wide avenue, following along the straight line from Pařížská Street and the bridge Čechův most all the way to Bubeneč. Koula also had a hand in designing Čechův most, built in 1905–08, and saw the avenue as a natural extension.

His plan would have meant cutting right through the rocky cliffs of Letná. He envisioned more than just a tunnel. Sketches and models show a massive two-sided colonnade, covered by a walkway on top, and lots of classical sculptures.

While the plan was never put into effect, a detailed plaster model can be found in the National Gallery in Prague’s permanent exhibition at Veletržní palác.

Still, the idea has its fans. “Personally, I regret that Jan Koula’s proposal for the Letná excavation from 1907, which was to build on the monumental bridge Čechův most, by the same author, was not realized. Fifty years later, a monument to Josef Stalin was built in its place, and the excavation was replaced by the Letná Tunnel several hundred meters further. Čechův most actually leads nowhere and ends in a green slope,” architect Petr Kučera told the newspaper Metro in 2017 when plans for unbuilt projects were exhibited.

The Blob

One of the biggest controversies of recent years was for the Blob, a proposed National Library building that was supposed to be built in Letná Plain. The official name of the project is the Eye Over Prague.

The Blob was the winner of an architectural contest in 2007 to create an additional space for the National Library (NK).

After architect Jan Kaplický won the NK architectural contest, then-president Václav Klaus and Prague’s then-mayor Pavel Bém (ODS) opposed its construction, and publicly ridiculed the proposal.

Kaplický died in 2009, still hoping that the Eye Over Prague would be built, but opposition just grew stronger.

Some losing architects in the original contest claimed that the design did not meet the stated criteria. The Court of Appeals decided in 2015 that the winning proposal should have been disqualified. The Supreme Court upheld the decision, ruling that 3 million CZK should be paid to the losing architects to make up for the differences in prize money once the winner was excluded.

The Blob has made several appearances. A small version of its facade has been incorporated into a bus stop in Brno, and a video-mapping of its shape was projected onto a tent in 2015 during the Letní Letná theater festival in Prague’s Letná park, not far from the originally planned building site.

The current Prague City Hall administration has no interest in the Blob being made, and in January 2019 backed out of a new study on the feasibility of the project. The study had been commissioned by the previous city administration, in which Kaplický’s widow, Eliška Kaplický Fuchsová, had served as a city councilor for the ANO party until October 2018.

The plans have since been turned over the state, on the condition that if it is built it will be on the original site, and that architects from Kaplický’s firm Future Systems would supervise any future development.

Quick facts:

- Letná park began as a military camp in middle ages, and was later a vineyard. It did not become a park until the 19th century.

- An irrigation tunnel built by Emperor Rudolf II runs under Letná all the way to Stromovka. The tunnel is still maintained but not open to the public.

View from Hanavský Pavilion. via Raymond Johnston - The neo-Baroque restaurant Hanavský Pavilion was built for the 1891 General Land Centennial Exhibition, and was the first cast iron frame building in Prague. It originally stood in the fairgrounds (Výstaviště ) in Holešovice, but was dismantled and moved after the fair ended. The front of the restaurant has a good vantage point for photos of the Vltava, which can be seen on postcards.

- The carousel in Letná is the oldest of its type in Europe. It was built in 1892 in Vinohrady and moved to the park in 1894. The carousel was originally powered manually, with a person rotating the turntable by hand. By 1930 an electric motor was used. A new motor was installed in 1981, and the carousel rotated faster than previously due to increased power. The carousel was listed as protected heritage in 1991. It closed in 2006 due to damage, and restoration work began in 2017. So far, the horses have been refurbished.

- The two-story neo-Renaissance chateau Letenský zámeček was built in 1863 by Vojtěch Ignác Ullmann, and is a protected cultural monument.

- The neo-Baroque style Kramář Villa has and 56 rooms and between 1911 and ’14 was built for Karel Kramář, who would later be the first Czechoslovak prime minister. Since 1998, the villa has been the official residence of the prime minister of the Czech Republic.

- The brick wall behind Kramář Villa, called the bastion of St. Mary Magdalene, had a cannon on it from 1891 to 1911. Two artillery soldiers cannon would wait for a waving flag signal from the astronomical tower in the Klementinum, and fire the cannon at noon every day so people could set their watches. The practice ended when construction began on the Kramář Villa, since nobody wants a full-size cannon firing in their backyard.

Reading time: 9 minutes

Reading time: 9 minutes