In the aftermath of the Velvet Revolution, Prague, famously dubbed the Left Bank of the Nineties, attracted its fair share of aspiring expat authors. Many hoped to publish a novel based on their experiences; Caleb Crain is one of the few who managed this feat – albeit more than two decades after his original stay in the Czech capital.

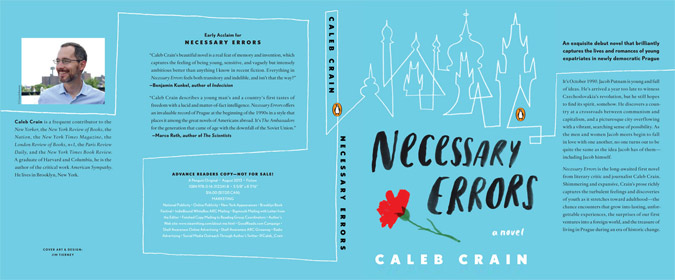

Crain’s first novel, Necessary Errors, is a stylistically restrained coming-of-age tale focusing on the emotional and sexual explorations of its protagonist, Jacob. The book, released in the US in August 2013 by publishing heavyweight Penguin, has already garnered considerable critical acclaim. We caught up with Caleb to find out more about his literary heroes, the connection between the creative process and the expat experience, and what it’s like upsetting Alain de Botton.

Your novel is suffused with your youthful impressions of Prague. Do you still have ties with the Czech Republic? If so, how do you feel it’s changed since the revolution?

The last time I was in the Czech Republic as the summer of 1993, and it seemed to me then that it had already changed remarkably, so I can only imagine how different it is now. In photos that friends send me, Prague looks much brighter than I recall (but of course camera technology has changed, too, in the last couple of decades). While I was writing, I ruled out any trips to Prague because I didn’t want my memory of the early days to be tampered with by later impressions, but now that the book is finished, I do wish I could visit again.

You’re working in a long line of illustrious US literary expatriates; at least one review has remarked on your debt to Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. Did you have any particular literary models or mentors in mind? What do you think being an expatriate adds to the creative process?

Sending a relative innocent into unfamiliar territory is an awfully convenient setup for a novelist, because it supplies the main character with a motive for observing closely: Everything is strange and new. While I was writing, I re-read Henry James, Alice in Wonderland, and Christopher Isherwood but I think it was more because I like them and found a sort of comfort in them than because I was trying to model my writing on theirs. Still, I’m sure they left a trace.

Jacob, the main character, is trying to figure out who he is, but so are the Czechs, who have just been through a revolution. Can you talk about the parallels between their identity crises?

I’m hoping the reader will see the parallels and also see through them. Jacob is somewhere between childhood and adulthood, and the Czechs are somewhere between communism and capitalism, but it isn’t quite as simple as dependency on the one hand and independence on the other. Capitalism isn’t developmentally inevitable after communism, the way that adulthood is after childhood. In fact, the next stage in Czechoslovakia’s economic life turned out to be something not quite as benevolent as the capitalism we’re familiar with here in America (even allowing for the fact that not everyone thinks of American capitalism as benevolent). Nor is adulthood itself all it’s cracked up to be. The psychologist Erik Erikson came up with the term “psychosocial moratorium” to describe the state of fending off for as long as one can the social definitions and conventional expectations that come with adulthood. The nontechnical term for the state is “bohemia”.

What role does history play in the novel?

Jacob, the main character, has the idea that he’s arrived in Prague too late to experience the spirit of Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, which took place a year before. I think that’s part of what it feels like to be young: the sense that it’s already too late, that the story is over and it’s not clear you have a place in it. But another part of being young is the sense that a new world is dawning and that you’re one of the few who will get to see it. In the aftermath of the Berlin Wall, both ideas were very much in the air. So were a lot of hints of the history that hadn’t unfolded yet: a war in Iraq, anxiety about terrorism, a triumphalist note among politicians on the right, the first suggestions of gay marriage.

Your professional writing career before Necessary Errors has been focused in the non-fiction sphere, including, of course, the infamous book review in the New York Times which provoked that extraordinary outburst from Alain De Botton who declared: “I will hate you until the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make.“ How you think the De Botton experience helped prepare you for the critical reception of Necessary Errors?

I’m afraid I have a policy of not commenting about that particular incident, other than to say that I stand by my original review. As a long-time reviewer, I may be more aware than other authors that reviews are written by human beings, and I might be more willing, on that account, to take them with a grain of salt. I don’t think reviews are addressed to authors, though of course authors read them (I read mine, anyway); reviews are addressed to a book’s prospective readers. That said, the reception of my novel hasn’t been a very good test of my philosophy, because I’ve really lucked out. The reviews have been extraordinarily thoughtful and generous in spirit, and I feel very grateful for them.

Were you influenced by Czech novels?

Not quite as much as I thought I would be. I’ve had a fair amount of engagement with Czech literature over the years. A long time ago, I translated a campaign biography about Václav Havel and about half a dozen short stories by other Czech writers, and I’ve written essays about Havel, who’s a hero of mine, as well as about Milan Kundera. I’ve read and loved novels by Jiří Weil, Karel Čapek, Ladislav Fuks. Maybe Jacob’s innocence owes something to the innocence of some of Bohumil Hrabal’s heroes?

How’s your Czech?

Nowadays, pretty rusty. I took advantage of the license of fiction and let Jacob become, by the end of the novel, rather better at Czech than I ever became myself. Whenever characters spoke to each other in Czech, I wrote their dialogue in Czech first. But since I then proceeded to translate it myself, no one will ever know how many mistakes I made.

First novels are often (at least partially) autobiographical. To what extent is Jacob a version of you?

If the novel is ever translated into Czech, I’ve thought of giving it the title “Bylo nebylo,” a phrase that literally means, “There was and there wasn’t,” but is usually rendered in English as “Once upon a time….”

***

Further reading:

Read Caleb Crain’s New Yorker essay “My Teacher’s Shadow” about his relationship with eminent Czech translator Peter Kussi.

Read an excerpt from Necessary Errors on the US Penguin website.

Have you read Crain’s novel? Tell us what you think.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes