The environmental group Greenpeace opened a branch in what is now the Czech Republic 30 years ago, but its activist roots go back even further.

In 1991, Greenpeace International expanded into Czechoslovakia, its first country in Central and Eastern Europe and first post-communist country.

When Czechoslovakia split two years later, so did the Greenpeace branch. The Slovak branch would merge with regional offices of other countries into Greenpeace CEE. But Greenpeace Česká republika still remains independent. The Czech branch has mostly focused on toxic pollution and energy, especially coal.

While the local branch in 2021 celebrated three decades, the international Greenpeace has been around for half a century. It incorporated in 1971 in Canada as the Don't Make a Wave Committee, and its first major action was a protest of a nuclear bomb test at an island off the coast of Alaska.

A group from the committee attempted to reach the island on a boat temporarily renamed Greenpeace, but was blocked by the U.S. Coast Guard. The group adopted the name Greenpeace for itself the next year, and expanded the scope of its goals.

Long before the Czech branch could be legally established, Greenpeace began to stage events behind the Iron Curtain. In 1984, the group took a stand against acid rain caused by coal-burning power plants in northern Bohemia, Poland, and East Germany. Greenpeace activists from West Germany climbed a chimney at a coal-burning plant in Karlovy Vary and began to hang banners spelling “STOP.”

Militia members fired at the protesters but did not injure anyone. The activists were expelled from the country on the same day, as the communist authorities wanted to avoid publicity.

In 1987, one year after the Chernobyl nuclear accident, Greenpeace activists from Austria hung a banner on the National Museum in Prague, warning of the potential danger of the planned nuclear power plant at Temelín. The protesters were arrested and immediately deported.

The poor state of the environment was obvious to many in Czechoslovakia, despite efforts to keep it secret. Environmental concerns were among the issues in protests leading up to the Velvet Revolution, not only in Prague but also in places like Teplice, which had a severe smog problem.

Just after the Velvet Revolution, on Dec. 11, 1989, a bus from the Austrian branch of Greenpeace arrived on Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Over the course of a few days, activists distributed thousands of stickers and information leaflets, while collecting nearly 80,000 signatures on a petition against nuclear energy.

The bus, which had a laboratory on board, took trips around the country in December 1989 and took samples of air, water, and soil. The results were dire, and Greenpeace sent them to authorities.

The warm reception the bus received prompted the idea of establishing a Greenpeace branch in Czechoslovakia. But each new branch must be approved by Greenpeace International. Although Central and Eastern Europe was an interesting region, it was not the only international priority. The Austrians continued their activities on Czechoslovak territory.

During this time, Greenpeace representatives learned about a uranium ore processing plant called MAPE Mydlovary, located between some small villages in the České Budějovice region, not far from the German border. Locals said radioactive material leaked from the plant in the 1960s, but communist authorities covered it up. The cancer rate in the region had increased since the leak. Greenpeace became interested in the case and a small Greenpeace office was established in České Budějovice.

At the end of January 1990, Greenpeace began to publish information about the radioactive leak. The Austrian press seized on the issue, while the Czech media was skeptical. Declassified records later confirmed that there was indeed a medium-sized leak from the site in 1965 and two smaller ones in the 1980s. The independent Austrian Institute for Ecology also confirmed that the Mydlovary area was contaminated.

On April 26, 1990, the fourth anniversary of the Chernobyl accident, 13 activists climbed the 155-meter-high cooling tower of the Temelín nuclear power plant, which was still under construction. They stayed for nine hours and hung a huge banner reading "Stop CSFRnobyl!" The reference was a portmanteau of Czech and Slovak Federative Republic, the formal name for Czechoslovakia from 1990 to ’92, and Chernobyl.

Greenpeace had been critical of the Temelín reactor in part because it was an untested mix of Soviet and American designs. The main argument for Temelín was that it would create a source of cheap energy while reducing reliance on dirty coal. Temelín wound up being about twice as expensive as planned, and only two of the planned four reactors were built. The coal-fired power plants that Temelín was supposed to have replaced remained in operation, while the Czech Republic has instead turned into an energy exporter.

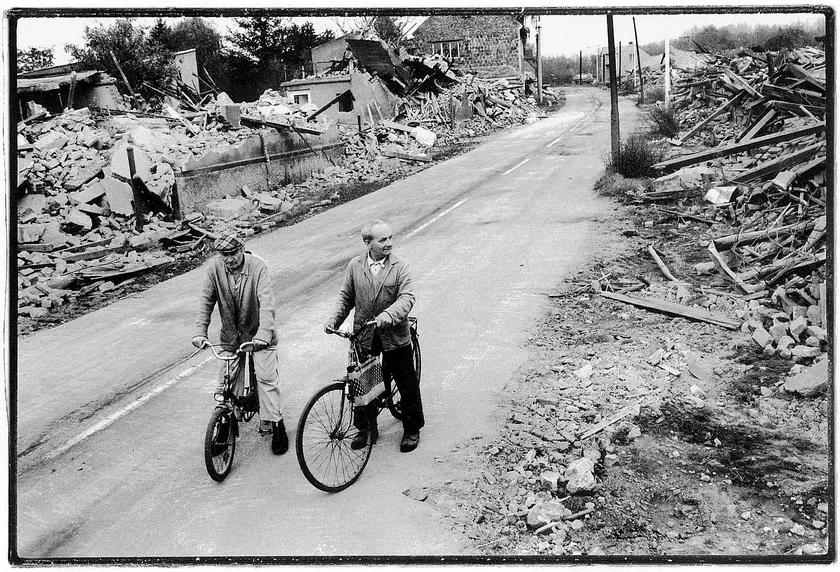

There were some changes, though. Technical improvements took place at large coal-fired power plants to at least reduce pollution. Nature protection laws were passed, including coal mining limits. But these were not enough to save the village of Libkovice. Greenpeace and other activists tried to protect the village from planned demolition but were unsuccessful. In the end, the coal under Libkovice was never mined, so the destruction was pointless.

Greenpeace together with other environmental groups were more successful in preserving the village of Horní Jiřetín, which was also threatened by the expansion of the mines. The government in 2015 made a compromise that saved Horní Jiřetín but allowed mine to expand elsewhere. Greenpeace has since gone on the offensive seeking an end to coal mining and burning by 2030.

The Czech branch of Greenpeace has also been involved in international issues, such as efforts to stop Arctic drilling. These involved having a replica polar bear called Paula in motion at landmarks such as Prague’s Charles Bridge and the historical center of Český Krumlov. The bear was sued to help get signatures on petitions, for example. Greenpeace International has been campaigning to save the Arctic since 2012. The area has been hit hard by climate change, with much of the icecap now vanishing in the summer.

The campaign is more than just publicity stunts. Greenpeace branches have been successful in courts in Canada and Norway to stop exploitation of the Arctic. The group also helped to stop Shell from Arctic drilling and put pressure on the US government to protect the areas under American control.

Greenpeace has long been trying to hold oil companies such as Shell accountable for climate change. Part of the efforts included lobbying toymaker LEGO to end its long cooperation with Shell to include the Shell logo on toy gas stations and cars. The Czech branch of Greenpeace protested at the LEGO factory in Kladno, staging a fake oil spill and giving speech balloons to LEGO characters. The characters questioned why LEGO helped Shell to clean up its image.

Greenpeace won a significant victory in this case, with LEGO deciding not to renew its cooperation with the oil giant in 2014.

Despite some victories, a lot remains to be done, and both the Czech branch of Greenpeace and Greenpeace International remain active in trying to urge both the European Union and local governments to shift to sustainable policies.

This article was written in cooperation with Greenpeace Czech Republic. Read more about our partner content policies here.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes