Nov. 17 marks the Day of the Struggle for Freedom and Democracy and International Student Day. It's also the 33rd anniversary of the beginning of the Velvet Revolution when on this day in 1989, thousands of students flooded Prague’s Wenceslas Square to protest police brutality, triggering the eventual fall of the communist regime.

What was life like then for the average student and how does it compare with the student experience today? In the 1980s, free speech, personal mobility, and access to Western media were all severely constrained. Yet, some aspects challenges faced by students then still resonate with the younger generation today.

Student travel and post-graduate life

Travel to Western European countries was nearly impossible for students from Czechoslovakia and involved pre-approval from the authorities, an exit visa, and only very limited foreign-exchange funds. Students could visit other communist countries but even travel to countries within the bloc – Poland, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia – involved hurdles and excess bureaucracy.

Once graduation was over mandatory military service awaited students of the 1980s. Military school – often done once per week for two years – was required of graduates who were then forced to serve one year at a military post thereafter.

Today there are over 300,000 students studying in Czechia. Most with the ability to go on study-abroad exchanges in Europe or even to other continents.

Since its establishment, a total of 350,000 Czechs have been able to participate in the Erasmus exchange program, which today includes freedom of travel and study in 33 different nations in Europe.

Today, graduates have a brighter future. The Czech Republic hosts around 100,000 foreign companies, and the country is a beacon of possibility for many international students: half of them remain in Czechia to work after graduation.

That said, about 9 in 10 students in Czechia currently work to keep their heads above water, with the vast majority (over 70 percent) reporting financial struggles. The cost-of-living crisis amid skyrocketing rental prices and inflation has also made it difficult for students to find housing or afford to live in Prague.

Access to information and languages

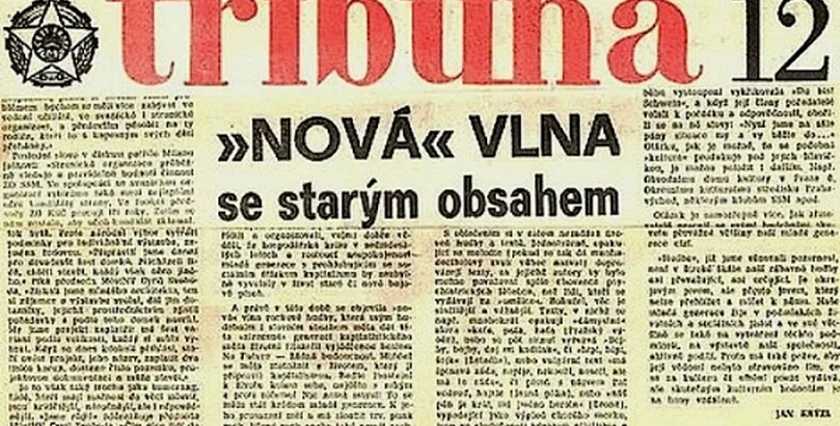

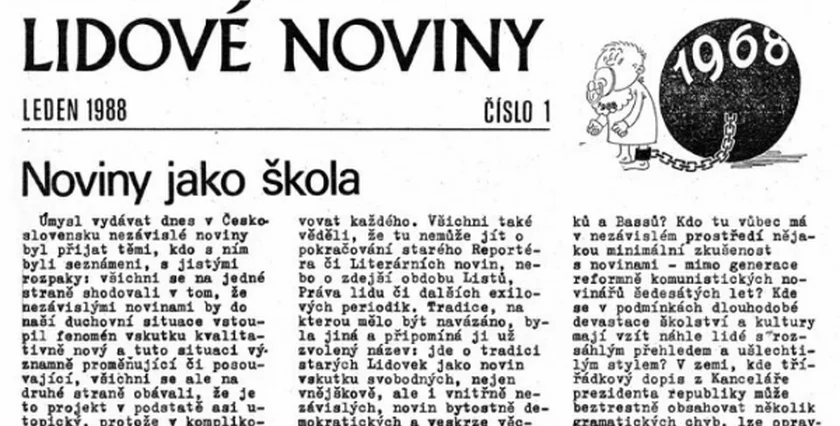

Students of the 1980s were widely exposed to propaganda: news publications and journals such as Mladá fronta, Svobodné slovo, and Rudé právo were mouthpieces of the KSČ. Western radio stations (such as those of Radio Free Europe) were jammed, and television was run by the state.

In the sphere of universities – institutions where new information and perspectives should be fostered – any free debate was stifled. Lecturers would hail the benefits and superiority of the Soviet Union and the KSČ, regardless of the subject studied. Knowledge of Russian in the 1980s was a necessity for “normal” university life.

Today the birth of the internet and technological advances have simplified learning. Increased globalization and the growing number of international businesses have opened doors to a wide range of opportunities: both within Czech borders and abroad. Students have the ability to learn languages other than Russian and pursue their own creative or academic interests without inhibition or obstruction.

But while it's easier for students in modern Czechia to access information, they are now inundated with it and must carefully navigate what can sometimes be a minefield of deception in the web sphere.

Tereza Fojtová, Media Communication Manager at Masaryk University“We believe that today, when Europe is experiencing a severe test of trust in democratic institutions as a result of the Russian war in Ukraine, there is a need to talk more about freedom of speech and the media. Wars are no longer only fought on the battlefield, but also on the information field."

According to František Vrabel, the former head of anti-disinformation firm Semantic Visions, the "Czech Republic is at the peak of the disinformation war," as reported in perpetuum.cz. A report last year found that 66 percent of Czechs encounter fake news online.

One recent example of disinformation affecting students in Czechia was the fake news of Russian students facing expulsion from Czech universities in the spring of this year. Amid Covid-19, students have also been victims of pandemic-related fake news. At the beginning of this month, six Czech universities convened to discuss the pressing issue of disinformation in academia.

Voicing dissent then and now

Compared to the liberties enjoyed by the average student in Czechia today, young people over three decades ago lived a life of persecution and subjugation.

Those who even dared speak out against the regime would face dear consequences; some would be expelled from university, others sent to prison. The Czechoslovak Press and Information Office, run by the KSČ, would monitor materials for any possible dissidence and censored items where necessary.

Spies were also everywhere at university: I interviewed a former student of VŠE in the 1980s, who told me that almost every class had one. Any words of dissent risked being reported to the State Security (StB). Often, family members would be dragged into a case of dissent and also risk punishment.

Those captured by the authorities for publishing – or reading – dissident works would face harsh punishment from the authorities. The case of David Kabzan, who was brutally interrogated and beaten by the StB for involvement with dissenting literature when he was a student, is a sad example.

- David Kabzan, a dissident in the 1980s"The Estébás [StB spies] followed me everywhere...at school, on the street. After three-quarters of a year at school, it was unbearable, so I moved out. That got me into dissent."

Today, students in Czechia have the right to free protests and can voice alternative views. Demonstrations occurring throughout this week against climate change epitomize the freedom of speech that communist-era students had no privilege of.

However, the issues behind these protests are dire and today's students must reckon with climate change, war, and a different kind of repression – recent student-led protests have drawn attention to the Russian-Ukraine war, discrimination faced by the LGBTQ+ community, as well as the country's burgeoning #metoo movement which has rippled through Czechia's student population.

Linking past and present

In the decades since the 1980s and Velvet Revolution, life has fundamentally transformed. Students today enjoy luxuries that those of the past could barely imagine: free speech, travel opportunities, access to new technology, and more. Today students in Czechia no longer need to live in fear of a spy reporting their activities or being forced into military action.

What links Czech students of the past and present is the desire to learn new things and voice their true state of mind on current affairs. Those who took part in the protests 33 years ago can look back with pride that they were able to help students today achieve these crucial freedoms, and, amid the backdrop of new challenges, pass the torch to the next generation.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes