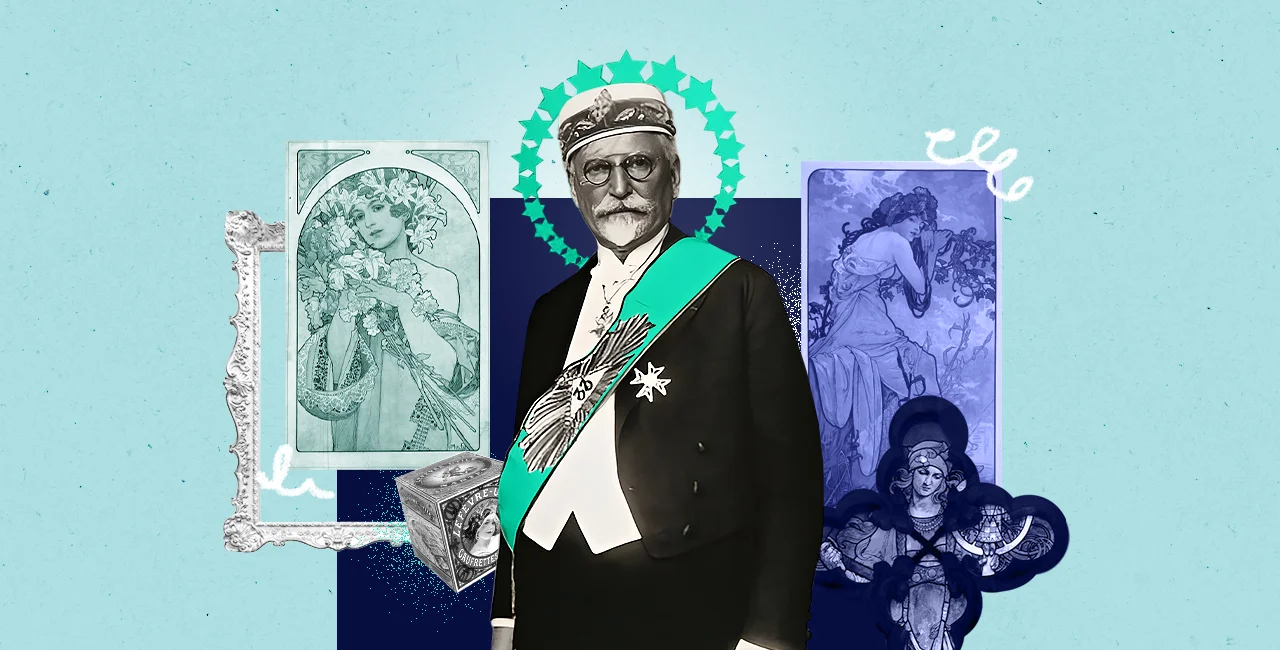

Art Nouveau painter and poster maker Alfons Mucha was born 163 years ago on July 24, 1860, in Moravia, but he spent much of his career in Prague, leaving behind his artwork and a long list of places associated with key moments of his life.

A good starting place to see his work is Obecní dům. Mucha’s paintings on the walls and ceiling in the Mayor’s Hall date to 1910–11 and show historical figures who embodied Slavic virtues and a large work depicting Slavic unity. The hall is included in the tour of the building. Currently, Obecní dům is also home to the iMucha exhibit, with posters and art from the collection of tennis star Ivan Lendl. This makes it a sort of one-stop shop to get an overview.

More of his work is on permanent display in another nearby building. Since 1998, the Mucha family has operated the Mucha Museum with more of his work at Panská 7. The extensive collection is divided into seven sections covering different aspects and themes from his career.

A notable commission that the public can still see is the stained glass window in St. Vitus’ Cathedral in Prague Castle. The Czech bank Slavia asked Mucha to make the window so they could show their support for the Cathedral, which had just been completed at the time. The window shows St. Wenceslas and his grandmother St. Ludmila, as well as the Slavic missionaries Sts. Cyril and Methodius.

One of the true gems of Prague’s Art Nouveau architecture is the Hlahol Association House at Masarykovo nábř. 16, where the choral association of that name is still based today. Inside the building, you can find Mucha’s large lunette canvas on the theme of Song, which the painter began in 1921 and completed 13 years later. The canvas is in the great hall on the building's ground floor. This is also one of the harder works to see, as the building is open to the public only occasionally for concerts or events.

Buildings in Mucha's life

Several buildings are associated with Mucha, but don’t bear traces of his art. While the National Theatre has decorations by several notable artists, Mucha is not among them, although the building played a big role in Mucha’s life. When French sculptor Auguste Rodin visited Prague in 1902 for an exhibition of his works, one of the side events was a visit to the theater, during which Mucha served as a guide and translator for his friend.

Sales Lead | High-Performance Computing & AI

At this event, Mucha first saw his future wife Marie Chytilová, a student of applied art. They didn’t become close until a year later when they met again in Paris and she became his pupil, and married in 1906 at Strahov in the Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady.

Across the street from the theater is the Topič Salon. In its early days, the salon occupied a space in the courtyard. In 1897, the courtyard space hosted not only Mucha’s first solo exhibition in Prague but also the city’s first Art Nouveau show. Exhibits included his posters for actress Sarah Bernhardt and other subjects plus some of his book illustrations. The current elaborately decorated Topič building, located next to where the courtyard gallery used to stand, dates to 1906. Mucha, though, did not participate in its decor.

Rodin’s visit did lead to a notable work of Mucha’s art that people can still see. Mucha escorted Rodin to the Old Town Hall, which at that time still served as City Hall. During the meeting between the then-mayor, Vladimír Srb, and Rodin, the mayor first suggested that Mucha participate in decorating Obecní dům.

Banknotes, stamps, and ice cream

On Wenceslas Square, at Vodičkova Street, you can find Ligna Palace, which also has some Art Nouveau details on the facade, although they are not Mucha's creations. During the First Republic era, Mucha used the top floor as a studio where he designed stamps and banknotes. He also made his first sketches for the Slav Epic there.

Some of his banknote designs can be seen in the visitor center of the Czech National Bank on Na Příkopě Street while stamps are at the Postal Museum.

Mucha’s daughter, Jaroslava, said that she posed so long in the summer heat to be the face on the 10 Czechoslovak crown banknote that she passed out from exhaustion. The artist took her to the Myšák sweet shop at Vodičkova 31 for strawberry ice cream after she recovered.

The ongoing saga of the Slav Epic

Mucha has a mixed history with the Klementinum, the large complex at the Old Town side of Charles Bridge. It housed the Academy of Fine Arts up until 1886. Mucha applied and was rejected twice, with the people in charge suggesting he find another line of work. But in 1919, the large space that is now used by the National Library gave people their first look at some of the Slav Epic and showed five of the finished 11 large-scale paintings.

While Mucha worked on much of the Slav Epic in at the Zbiroh château in Central Bohemia, he completed it in Prague in the former chapel of a school called U Studánky located in Umělecká 8 in Prague’s Holešovice district. He worked on the final touches between 1926 and 1928. The 20 large-scale paintings are now displayed in Moravský Krumlov in South Moravia. They should be displayed in Prague once a location is established, though legal issues over the ownership and the final permanent location are dragging on.

The complete Slav Epic was displayed for the first time in 1928 in Veletržní palác, which is now part of National Gallery Prague. The gallery again displayed the paintings between 2012 and 2016.

Mucha's homes and studios

There is a metal plaque with Mucha’s bust in Malá Strana at Thunovská 25 (Palác pánů z Hradce), where he lived from 1911 to ’24. The building itself, on a dead-end part of the street, is in bad disrepair and not open to the public.

He also lived in Prague’s Bubeneč district at the villa at V Tišině 4 from 1928 to the end of his life in 1939. Mucha hired architect Bohumil Hypšman, who also made what is now the Health Ministry, to design the house. It had a studio on the upper floor.

The house was used by the Nazis and later was nationalized by the communists. It was returned to the Mucha family after the Velvet Revolution and is now rented to Ghana for use as its embassy.

The Czech branch of the Freemasons in the early 1900s had its headquarters at Husova 9. Mucha designed their emblems, seals, letterheads, and diplomas. In 1925 he also wrote a book on Freemasonry to coincide with the 333rd anniversary of the birth of Jan Amos Komenský.

The final place in Prague associated with Mucha is Slavín, the tomb in the Vyšehrad Cemetery reserved for famous Czechs. Mucha died of pneumonia on July 14, 1939. His health declined after a long and grueling interrogation by the Nazis. He was under suspicion both for being a Slav nationalist and a Freemason. A large crown attended his interment at Slavín, despite a ban on public gatherings.

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes

Czech

Czech

Norwegian

Norwegian

French

French