Among Prague’s many landmarks, it’s fairly safe to say that the Nusle Bridge or viaduct (Nuselský most) does not have the best reputation.

The gargantuan bridge, which dwarfs the rooftops of the Nusle neighborhood below, is infamous for several reasons. Sadly, it is perhaps most famous as a suicide spot, and it also became the brief center of global attention in September 2000, featuring in TV images beamed around the world during confrontations between police and protesters at the IMF/World Bank Summit. And many Praguers simply dislike the viaduct, regarding it as an eyesore.

But whatever one’s views on its aesthetics, it has to be admitted that the Nusle Bridge is impressive. And as the bridge celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, now is an ideal time to look at the back story of this relative newcomer to the Prague scene, but one that has become very much part of the townscape. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine Prague without the landmark.

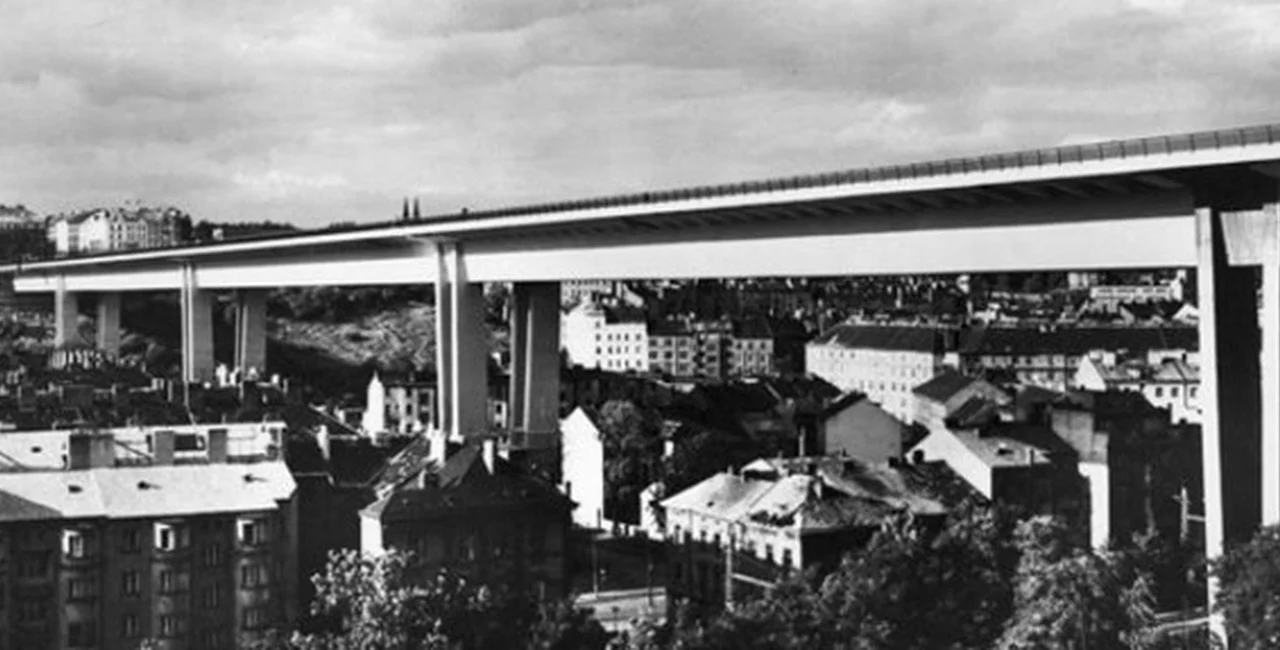

Nusle Bridge is an impressive sight from all angles, especially when approached from the long streets running underneath it and perpendicular to it. The structure’s vital statistics are equally impressive: up to 43 meters high, 485 meters long, and 27 meters wide. The bridge has four spans and is borne on four sets of concrete pillars.

The bridge bears the country’s main highway, the D1 motorway, as well as a stretch of metro line C, between I P Pavlova and Vyšehrad stations. The trains run directly underneath the highway.

Although many people assume that the Nusle Bridge is the result of Communist-era planning, its story goes further back, to the First Czechoslovak Republic. Plans were made and competitions held for designs to span the relatively wide Botič valley, running east from the southern edge of New Town and separating it, Vinohrady, and Vršovice from Pankrác and the southwestern suburbs. A stream of the same name flows through the valley and is almost insignificant in comparison to the huge scale of the bridge. Ultimately, these projects came to nothing, and the Nusle Bridge story truly began in the early 1960s, as new housing estates in Pankrác grew up, prompting, among other things, the need for better transport links. In addition, the Communist government was carrying out major changes to the fabric of the Czech capital as part of its city development plans.

One aspect of this was the new highway, known as the magistrála, which became operational in the 1970s and 80s, cutting through swathes of the city centre including Wenceslas Square – the reason why the National Museum is divorced from the rest of the Square. The magistrála was to continue through the southwest of Prague, and under the plans for the road, it would span the Botič valley. A team of engineers were appointed, including architect Stanislav Hubička, and construction of the Nusle Bridge began in 1967; 17 tenement blocks in Nusle were demolished as part of the construction process. The structure, officially categorized as a box girder bridge, was built from pre-stressed concrete and opened six years later, on 22 February 1973. Somewhat predictably, it was named after a member of the Communist pantheon, Klement Gottwald, Czechoslovakia’s loathed “first working-class president“.

In May 1974, the first stretch of the Prague metro opened, from Sokolovská (now Florenc) to Pankrác; trains ran under the bridge via Gottwaldova (now Vyšehrad) station. Originally, the bridge was designed to bear trams or metro carriages of a specific weight, but the plans changed, and Soviet-built wagons, which were twice as heavy as those originally intended, were ordered for the Prague metro, a cause of much resentment among the engineers. Consequently, structural repairs using steel frames were necessary, and the platforms of metro stations had to be redesigned.

Sales Lead | High-Performance Computing & AI

Translations Project Manager | PART TIME

Another famous story about the Nusle Bridge relates to the squad of 80 Soviet-built tanks that crossed it, officially to test whether the bridge could cope with heavy traffic. Some believe, though, that the real reason was more sinister, part of a plan to quash any dissent with military force. In an interview, architect Stanislav Hubička said that he didn’t know if the story was true, but he wouldn’t rule out an ulterior motive.

Inevitably, mention has to be made of the bridge’s darker side. It has gained a reputation as a suicide spot, and estimates by put the number of attempted suicides at 200 to 300 since it was built. In 1997 the city authorities added tall chain link fence railings along the sidewalks, and in 2007 additions were made in a further attempt to prevent suicides.

Today, the Nusle Bridge (as it is known after being renamed in 1990), is of key importance in the Prague and Czech transport network, forming a link between the city center and the southwestern suburbs, as well the connection between Prague and the Czech Republic’s second city of Brno. Thousands of commuters pass over the bridge every day, and thousands more travel through the bridge every day on the metro.

The Prague metro continues to grow, and plans are afoot for adding another line to the metro network, including a route that would run from Náměstí míru on line A to Pisnice Depot on the southern fringe Prague. At the moment, nothing is clear, but it appears that the line will connect with line C at Pankrác.

On a personal level, I have an enduring fascination with the Nusle Bridge, because I have vivid memories of it from my first trip to Prague, on a university field trip way back in the heady days of 1993. We had arrived in the city late at night after a tortuous rigmarole of a two-day journey from the United Kingdom. My first recollection of Prague was distinctly down-at-heel (as it was then) Anděl, which one of my friends promptly labeled “The Twilight Zone”. Soon we crossed Palackého most and as the Castle view emerged we gasped in amazement.

The next Prague landmark to elicit a response, this time of a less favourable kind, was the Nusle Bridge, and I recall phrases like “War of the Worlds” and “sci-fi” being bandied about. Indeed, the bridge seemed alarming, nightmarish, as it loomed ever larger, the gangly concrete limbs striding over peeling blocks of tenements. Although our imaginations were a little overworked thanks to tiredness, the bridge was still awe-inspiring when we whizzed over it a few days later. And even today, when traveling on metro line C, I still feel a twinge of amazement as I enjoy the brief interlude of light and scenery at Vyšehrad, before the train is swallowed up by the darkness again.

Related articles

- 10 Travel Articles That’ll Get You Excited for Autumn In the Czech Republic

- VIDEO: Amazing Recreation of 14th-Century Construction of Charles Bridge

- Prague Is the Cheapest City In Europe for Ballet, Opera, Art

- Český Krumlov Mulls Over Charging Tourists a Toll

- New Travel Guide Puts Czech Monasteries On the Map

Reading time: 5 minutes

Reading time: 5 minutes

Swedish

Swedish

French

French

German

German